Reading Back #3: Ask the Reader

Like all good magazines, The Reader has its own problem page. Ours is called Ask The Reader. In every issue Brian Nellist gives thought to one particular reader’s question about their reading or their reading life. Here from issue 11 is a problem that many readers will recognise concerning the debate about reading for improvement or reading for pleasure.

ASK THE READER

Brian Nellist

Q

I go to Stratford regularly and read George Eliot and Anne Michaels for CE classes but for my own pleasure I used to read John le Carré and nowadays it’s John Grisham; in those complicated plots I forget everything else. Yet this is condemned as escapism. What’s wrong with that?

A

Calm down; don’t be so defensive. From what you have just said I rather suspect that you yourself could hazard a guess at two things that are slightly askew. It is not that you refer to Shakespeare as though he is a medicine to be taken for one’s mental health (‘regularly’) which is true in a way but rather that you are limiting the meaning not of Shakespeare but of pleasure. I am reminded of the use of the term by Wordsworth who is the great apostle of its gospel. In the ‘Preface’ to Lyrical Ballads he credits poetry with only a single limitation, ‘the necessity of giving immediate pleasure’. The harm comes from trivialising the word, he believes, because in essence man is a creature who seeks pleasure; ‘the grand elementary principle of pleasure by which he knows, and feels, and lives, and moves.’ Pleasure always involves the satisfaction of desires, so the argument goes, and the deepest pleasure must be given by what meets our profoundest, not our most immediate, needs. Hence for Wordsworth, surprisingly, all acts of sympathy, even with those in intense pain, whether in literature or in life, are grounded in pleasure because they embody our need for kinship, fellow feeling, pride in human endurance. Of course, we should not pervert this into pleasure in suffering itself but grant that in its acts of understanding literature encourages a tenderness and fineness of feeling that fulfils a need in us; ‘wherever we sympathise with pain it will be found that the sympathy is produced and carried on by subtle combinations with pleasure’. So, feel free to acknowledge that Stratford and Middlemarch, without any juvenile sense of schadenfreude, are also sources of pleasure.At the moment you are turning literature into hard slog for which you compensate by guilty weekends of holiday reading. As you know, the greatest pleasures demand effort as much as the greatest anything else. It is natural if you enjoy playing bowls that the pleasure will be increased if you work seriously at your game.

But the second thing, from what you say, that you are not taking seriously enough is that word ‘escapism’. To get out of gaol is generally classed as beneficial to the prisoner. All literature in its attempt to make sense of things, even in expressing the fear they make no sense at all, is to that extent a liberation from the cell of non-meaning. We use this accusation too easily. I note from the dictionary that Punch (!) in December, 1939, significant date of course, thought the reading of the big Victorian realist novel an ‘escape’; ‘Many a publisher has had the good idea of advising you to escape thoroughly by way of an eighthundred-and-fifty page novel about family life in the Victorian era.’ Yet I remember after World War II being told by someone from GCHQ (or whatever it was called then) that the World’s Classic Trollope had preserved for him a sense of moral normality that very directly helped to sustain a belief in what he was doing.

But I am evading the issue now, I agree, because your point concerns not the use to which we put books that are ambitious in their aims but what used to be called light literature, a branch of the entertainment industry, to be dismissive of it. Those complicated plots by which you ‘escape’ are often the means by which the sense of friends and foes are identified with good and evil but by complicated routes to make the belief tenable to our sceptical minds, so that their identities become fluid and there are crossovers between the categories. The modern thriller has to complicate the sense that judgement was once a lot easier yet the resolution of the plot, however tentatively, gives you the reassurance that in the end the balance works out on the right side. Popular literature is often close to myth in the clarity with which it will work out its resolutions and a part of your guilty delight in it, I suspect, is the desire for an easier life than more complicated literature allows. Fairy stories do that, of course, and John Grisham may be closer to ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’ than to Middlemarch but that does not make it necessarily suspect. Behind the excitements of the Lord of the Rings, for example, we notice that Sauron is destroyed less by action than by suffering, including Frodo’s own corruption, that indeed fighting is part of that corruption and that unless it is registered as suffering there is no value in the fight. When we read quickly for plot and event we do not necessarily register these things but that does not mean they are not being noted somewhere inside us or that we do not feel refreshed in consequence.

Yet if it is a pleasure sometimes to read quickly, be conscious that you may have to do that because otherwise not enough is going on to hold the attention and also to avoid being irritated by how much better you could have expressed it yourself. Inattention in the reader can begin as an excuse and end as a habit; take care that you do not blunt your capacity for still greater pleasure, Paradise Lost or Women in Love.

(Remember: you can purchase all of these books, plus many others, through The Reader Organisation's Online Bookshop.)

Share

Related Articles

We cannot just tell parents to read more. To truly improve children’s futures through reading, we need to properly support the adults around them to do so.

Responding to the Department of Education's announcement that 2026 will be a Year of Reading, The Reader's Managing Director Jemma…

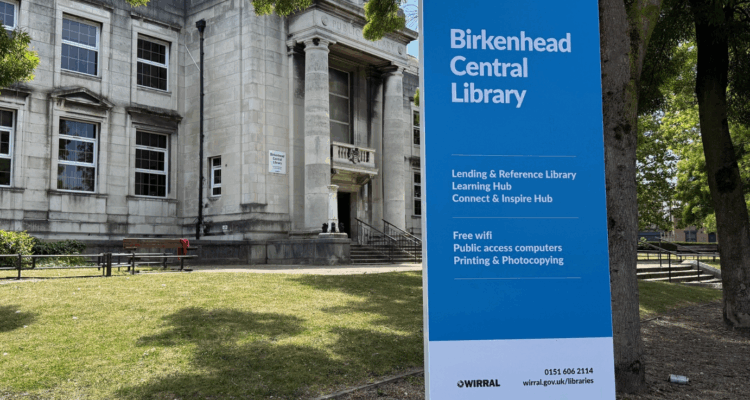

Shared Reading in Wirral Libraries: ‘As a kid people read stories to you but as an adult you lose that – and it’s a fantastic thing to do!’

Two Strategic Librarians for Wirral Libraries, Kathleen McKean and Diane Mitchell have been working in partnership with the UK’s largest…

Pat: ‘You don’t need to be an academic – it’s about going on your gut feeling about a story or poem’

National charity The Reader runs two popular weekly 90-minute Shared Reading group at one of the UK’s most innovative libraries,…