Reading Back #6: Our Spy in NY

According to George Bernard Shaw, Britain and America are two countries divided by a common language. Well, perhaps: but there's nothing common about the language (or indeed anything else) of Enid Stubin, our New York Editor, whose addictively incisive take on life and literature can be found in each issue of The Reader magazine. This from issue 16 is one of her very best, and gives us a final chance to cling desperately (and delusionally) to the dying days of summer. Enid is Assistant Professor of English at Kingsborough Community College of the City University of New York and Adjunct Professor of Humanities at NY University's School of Continuing and Professional Studies. But she's also...

Our Spy in NY

Enid Stubin

Summer reading: that prismatic prospect for nine-to-fivers, the leisure class, and those academics possessed of three-month vacations. I’ve always been resistant to or envious of the notion of seasonal reading – what, I wonder, do literate folks do the rest of the year? I refuse to make a list of books I’d like to collect in May, June, and July, when, as an adjunct, I’ve been teaching remedial writing throughout the supposedly idle and therefore idyllic months of college vacation. But in response to an early-August repertory-house screening of Visconti’s The Leopard, I pawed through my grimy shelves for the Pantheon paperback (I know it’s here somewhere) of the di Lampedusa novel. I couldn’t find it but did turn up a copy of Malamud’s A New Life, ‘the National Bestseller at $4.95, now 60 cents’, whose cover features a voluptuous odalisque sprawled among the haystacks of some collegiate pastoral and a Montgomery Clift lookalike turned away in existential torment. It’s one of those books I’d managed to read as a sullen adolescent before I could understand it. A word on its provenance on my double-stacked shelves: in 1965, when my brother was courting the young woman who is now his wife, I inherited a short list of titles – A New Life, McCarthy’s The Group, Updike’s Couples, and Nabokov’s Lolita – and was invited into a casual book club that has informed what tastes I have today. These books were sophisticated, literary, and racy, and the act of reading them seemed to invite me into an alluring, adult world of possibility. Recently my sister-in-law told me that they were chosen by her mother – an intriguing literary inheritance.

Because I’d last read A New Life as a pre-teen, I riffled through the now-brittle orangey pages of the Dell paperback and entered the world of S. Levin, academic refugee from New York City making his way westward to Cascadia College, where he finds a crucible of overheated departmental politics: conflicted loyalties to the freshman writing director who hired him, a catalogue of misfit colleagues, the utilitarian squelching of the humanities and humanism, aching sexual and philosophical loneliness. Why does no one talk about this wrenching comic novel, sad and satirical, authentic, and somehow defiantly exultant? Maybe because the world it illuminates is that of academe, and academic satire doesn’t sell. Maybe not even to academics. When I first read A New Life, the impression it made on me was immediate, but how could that be? The world it limned so sardonically wouldn’t be mine for decades. And yet it was a world I knew before I knew it.

Malamud and Levin were on my mind as I hurtled south and east to my new teaching job, no mere provisional adjunct gig (part-time instructional staff, anxious and uninsured, like to claim solidarity with jazz musicians) but a full-time, tenure-track position at the prettiest campus in the city University of New York system – ‘Four days a week at the beach’, as a friend termed it. Catch the number 6 to Bleecker, dash downstairs to Broadway-Lafayette for the B train, and take it to the end of the line, Brighton Beach, where the salt air intoxicates and the signs dazzle, even if three-quarters of them are incomprehensible. I found myself in front of the Caviar Kiosk, which offered comically huge tins of beluga, sevruga, and malossol, along with Brobdingnagian plastic containers of plebeian salmon roe. What wondrous life is this I lead!

But I had deeper connections to Brighton. As a child I would clamor to spend whole weeks of the summer in Brooklyn with my glamorous cousin Eileen, a spirited hoyden with the after-school and summer social schedule of an aluminum heiress. Although I lived in Far Rockaway, bordered by beach and bay, I routinely begged to visit East Flatbush, from which, provisioned with salami sandwiches, nectarines, and second-tier towels, we would set forth via bus (the B49 to Sheepshead Bay) for a day at tony1 Manhattan Beach. The sand was newer and coarser than the Rockaway stuff, but it reliably lacked the glittering green edges of broken soda bottles and the odd bit of latex detritus (‘What’s that?’ I’d ask one of my older brothers who, wise in the ways of the world, kept discreetly silent but hustled me on with a light blow to the back of the head). Eileen held court among her cronies, a posse of animated girls from Samuel J. Tilden High School. And I would come equipped with a squashy grownup paperback from her snazzy Danish-modern wall-unit: the autobiography of Gypsy Rose Lee (tidily titled Gypsy, to coincide with the release of the Natalie Wood film); Dr. Benjamin

Spock’s Baby and Child Care; Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind; the ‘deft and daring comic novel’ by John Tessitore, which provided the screenplay for That Touch of Mink (a favorite Doris Day vehicle, with Cary Grant on board); and if not the complete oeuvre of Harold Robbins, certainly The Major Phase: 71 Park Avenue, Never Love a Stranger, A Stone for Danny Fisher, and the magisterial Carpetbaggers. Propped up on one of my aunt’s chintz comforter covers and anointed with the musky orange glaze of Bain de Soleil (‘for the Saint Tropez tan’), I negotiated the perilous transition from vaudeville to burlesque, prepared some unfortunate toddler for the rigors of toilet training, and followed the picaresque reversals of Robbins’s gritty guys and vulnerable vixens. All the while I was inviting the solar radiation that would culminate, twenty-five years later, in the odd basal-cell carcinoma. Along with the Howard Beach shelf of modern masters, this reading shaped my literary choices long before I took up ‘serious’ literature seriously. Cheesy covers wrapped incandescent prose; a schlocky Bildungsroman offered a glimpse into the mysterious realm of adulthood; lurid blurbs trumpeted contemporary fiction that has endured. The crummy and the crafted both stayed with me.

Lugging a manila envelope filled with my benefits package (largely offers for ‘catastrophic’ insurance and long-term nursing care), course syllabi, departmental requirements, and the author-ization for an ID card that would affix my squinting, haggard visage for all time under plastic laminate, I sniffed the air of Oriental Boulevard like a spaniel, off to fresh woods and pastures new. Will Eileen’s daughter, now seven, one day open one of her mom’s books and find, sifting out of the crackly, acid-laden bindings, some antique sand from my orgies of summer reading? I hope so. Let the kid form her own canon.

--

1. [Ed.] ‘tony’ is American for ‘posh’. Enid explains: ‘Manhattan Beach is posher than most NY beaches and compared with my native Rockaway and Coney Island, it’s the Riviera.’

Share

Related Articles

We cannot just tell parents to read more. To truly improve children’s futures through reading, we need to properly support the adults around them to do so.

Responding to the Department of Education's announcement that 2026 will be a Year of Reading, The Reader's Managing Director Jemma…

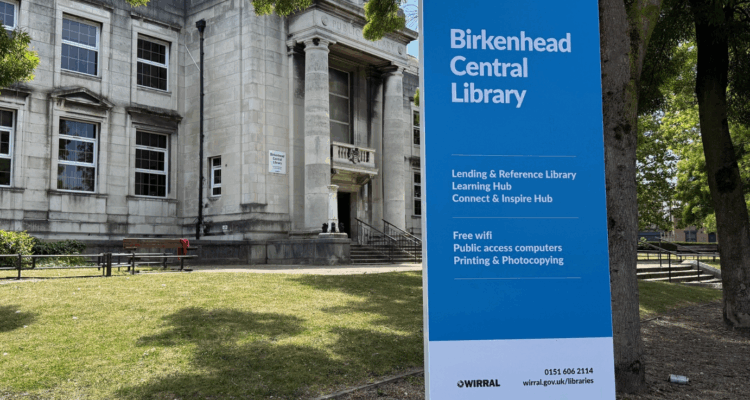

Shared Reading in Wirral Libraries: ‘As a kid people read stories to you but as an adult you lose that – and it’s a fantastic thing to do!’

Two Strategic Librarians for Wirral Libraries, Kathleen McKean and Diane Mitchell have been working in partnership with the UK’s largest…

Pat: ‘You don’t need to be an academic – it’s about going on your gut feeling about a story or poem’

National charity The Reader runs two popular weekly 90-minute Shared Reading group at one of the UK’s most innovative libraries,…