‘Something creative and unpredictable in an otherwise very controlled environment’: Shared Reading in Secure Mental Healthcare

Fiona Magee, research assistant based at CRILS – Centre for Research into Reading, Literature and Society – and Reader Leader in Criminal Justice settings, tells us about the latest presentation of research from The Reader and University of Liverpool.

For nearly a decade The Reader has been running Shared Reading groups in a range of settings within the Criminal Justice System including prisons, approved premises, high-security psychiatric hospitals, secure units and community justice initiatives.

Informal weekly groups provide the opportunity to listen, empathise and share reflections, giving offenders and ex-offenders new ways to tell their stories and move towards secondary desistance.

Earlier this month, in conjunction with CRILS (Centre for Research into Reading, Literature and Society, University of Liverpool), we brought together commissioners, psychologists and researchers into prison reform, prison officers, occupational therapists, and members of other reading agencies in London to explore the impact of Shared Reading in secure mental healthcare.

New research evidence

Speakers at the event included Nick Benefield (Personality Disorder advisor and Head of programme for National Offender Management Service in the UK Department of Health) and Alison Liebling from the Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge.

Professor Liebling and her research team shared the progress of their work carrying out an evaluation of Shared Reading in Psychologically Informed Planned Environements (PIPEs) while Professor Rhiannon Corcoran and Megan Watkins (in collaboration with the CRILS research team at the University of Liverpool) have been filming and analysing Shared Reading group-sessions delivered by psychiatrist, Dr Kathryn Naylor at Ashworth Hospital, Merseyside. What follows are some personal notes and memories.

A key theme was set out by Sarah Skett, Head of the Joint Offender Personality Disorder pathway for both NHS and HMPPS. Shared Reading, she argued, offered something creative and unpredictable within what was otherwise a very controlled environment. It was Shared Reading’s extra human ‘something’ in the midst of an often otherwise uniform regime that made a difference – using the group setting not just to protect people, but to take risks to explore thoughts and feelings that might cause pain.

Shared Reading ignites imagination

In the same spirit, Nick Benefield emphasised the role of imagination in the practice of Shared Reading. He defined imagination (or what he called ‘the imaginal mind’) as ‘everything that was against “not-thinking”’. This was a theme throughout the day as we started from discussing what Shared Reading was not: Shared Reading was not controlled (Sarah Skett). Shared Reading was the opposite of not-thinking (Nick Benefield). And Shared Reading was everything that was not ‘stuckness’ (as Alison Liebling put it).

Nick Benefield spoke powerfully of the way in which Shared Reading led to ‘the making of mind’. Many people in prison contexts could often only think in a way which felt fragmented, overlaid by anxiety, or repetitively hopeless. But, it has been found Shared Reading can ignite the power of thinking of possible alternatives, of experimenting, of thinking about new things from fresh perspectives.

He also spoke of what he called the ‘ping-pong’ effect when discussion comes alive in Shared Reading and the ball (as it were) is batted back and forth between participants in spontaneous community. This is part of finding of meaning – and without meaning, it does not seem to matter what you do.

‘Letting in’

In the same vein, Ph. D student Megan Watkins gave an account of the ‘thinking in real time’ that went on in the Ashworth reading group. In the films and transcripts she had assembled, one participant, discussing a poem about the power of sorrow, said ‘I have learnt to be sorrowful [then pausing] . . . maybe’. That extra word, noted Nick Benefield, was in place of an asserted positive outcome of rehabilitation: ‘I have learnt to be sorrowful!’. The ‘maybe’ was not just adding uncertainty, it was letting in the real, the more, the human complexity, come through, he said.

Alison Liebling also pointed to something more important than simple positive messages to be gained from Shared Reading. She described what she called her ‘heliotropic principle’ – the way that sunflowers, for example, turn to face the sun. In interviews and in group sessions, what was important was whatever gave warmth and energy. It was vital to start from that sense of life-seeking ‘movement’ before we could ever think of the bigger terms such as ‘growth’ or ‘change’. The team spoke of participants ‘moving between’ comfort and discomfort in a session. Kathryn Naylor also spoke of the difficulties her Ashworth group found in getting into the emotions in the text and in themselves.

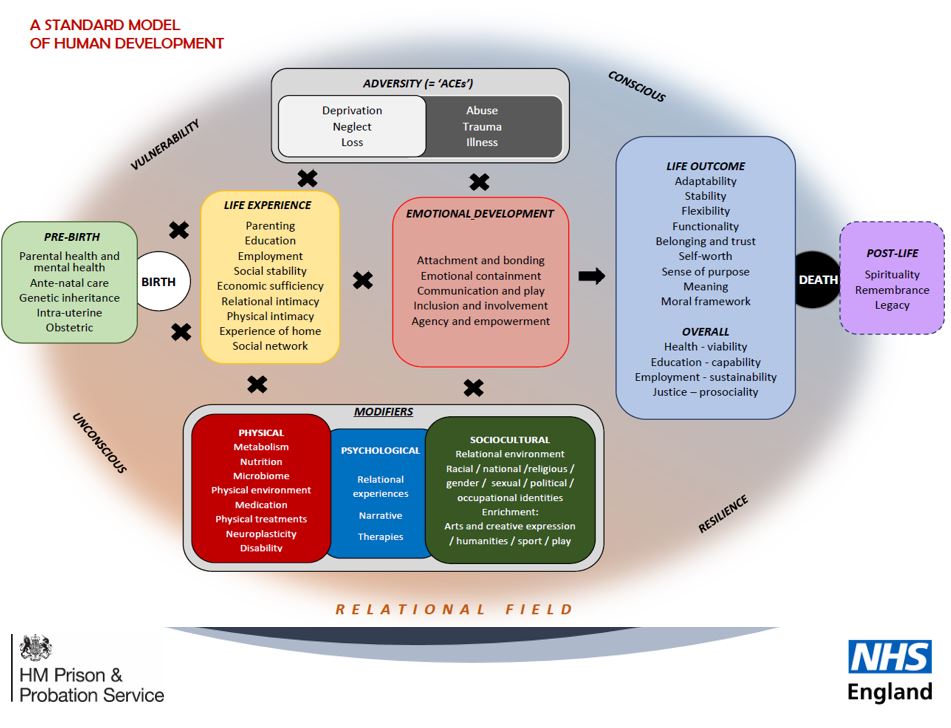

Nick and Alison both presented large-scale models. Nick Benefield mapped the complexity of the human journey from life to death, with all the factors and interactions that, for example, the staff in secure settings need to understand if they are do their work well. It was work in progress towards a model of human development.

Alison Liebling provided an early sight of a work in progress model for evaluation of arts interventions, the quantitative tool her group were using to survey the effectiveness of Shared Reading: MERG, ‘Measuring the Experience of Reading Groups. This was formed using 12 categories, the names of which were provided by prisoners themselves at interview.

Turning points

A key part of the day consisted in the discussion of specific case-histories and key moments from Shared Reading in practice. The Cambridge group offered the example of Grace in a group reading Edna St. Vincent Millay’s ‘Love is not all’. None of them liked it, everyone was dismissing of it. But Grace kept reading it, aloud to herself, until she quietly said ‘I think I get it’. She was, said the researcher, ‘oblivious’ to the others, who nonetheless stopped to listen to what she then had to report. This, Nick Benefield added, was the sign of an authentic person: ‘I have a mind’. For all the kindness and supportive sharing and democracy of the group experience, this aspect of individualism, of defiance of dismissal, was vital too. Megan Watkins likewise cited a participant in the Ashworth group saying that the people still felt alone but now alone together.

It did not matter, Benefield added finally, if you couldn’t get the participant to acknowledge that ‘something’ had happened. Too much analysis, too much questioning and consciousness might spoil the thing, he said. What was vital was the ability of staff to spot when something had happened, and then try to create the conditions for sustaining its continuance, whatever it was, without knowing where it would finally lead in terms of defined outcomes. That was life.

To find out more about the work of the Centre for Research into Reading, Literature and Society visit: https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/humanities-social-sciences-health-medicine-technology/

To find out more about The Reader's work in Criminal Justice, visit: https://www.thereader.org.uk/about/whatwedo/criminaljustice/

Share

Related Articles

Give a vulnerable child the joy and lifelong benefits of reading this Christmas

This Christmas, we're calling for donations to help us reach a £10,000 festive fundraising target. Funds raised will support the…

Community based solutions are needed to support the NHS to deal with mental health crisis

Geetha Rabindrakumar, our Director of Partnerships, Communities and Impact reflects on our research on reading habits and mental health and…

New research on what books can do for our mental health during a cost of living crisis

Our new survey of 2,000 people across the UK* reveals: Nearly two-fifths (38%) agree that they can relate to literature…