Heart of Darkness: men, women, and modernism

Yesterday I was contacted by writer Maggie Goren with a piece she had written in response to Raymond Tallis's story 'Heart of Darkness' which appeared in The Reader number 29. After Maggie submitted the piece I replied in a somewhat argumentative fashion and what followed over the course of the day was an email conversation reproduced here.

MG: Here is something I wrote a while back in response to a Raymond Tallis 'Heart of Darkness' short story in The Reader, which was equisite.

I recently re-read the Conrad classic and have this to say:

I would like to point out something probably blatantly obvious to most devotees of the Conrad novel which is that they belong strictly to a world of men. There is little or no place for the female of the species in them. And I wonder, on reflection, whether this was due to the most influential parts of Conrad's life as a seaman travelling around the world with other males? Or was it partly due to the period in which he lived and wrote, a time when male gender superiority was as natural to the writer as it was for example to the medical profession in which women were not expected to participate except as nurses.

The women who vaguely appear in Conrad's books do so either as figures representing a feminine mystique, 'woman with helmeted head and tawny cheeks' (a Klimptian image?) on the riverside as the boat is taking the sick Kurtz away or in the shadowy background as Kurtz' 'intended' waiting for the return of her admired adventurer or simply as attractive natives luring the Westerner in a straightforward and explicity sexual way? In the books I read no women figured as characters central to the plot or to any major moral or ethical problems besetting the central protagonists, story teller Marlow included.

In this respect I can see Graham Greene as a student of the Conradian 'morality tale' but to be fair perhaps both writers preferred to write about the sex they best understood. Even Hemingway, despite generous portrayals of tender or tough heroines, left the important moral dilemmas to the men. It was the job of the women only to reflect on or make pithy judgements about this active male moral highground.

Formidable predecessors such as Shakespeare, Dickens, Tolstoy, Hawthorne, Garcia Marquez, De Berniere among other writers understood or understand women as morally involved persons, giving them prominent roles to play. But Conrad, who sadly lost the first woman in a man's life, his mother, before he was five, avoided them as a writer it seems.

Perhaps it was this lack of gender balance in his life and work that created the shadow of pessimism, the alienation and the loneliness which are central to all Conrad's great works of fiction. Being out of touch with the feminine often, I feel, leaves a man without a positive and life-enhancing element, without solid roots in the earth from which he sprang.

CR: I must say I subscribe to the view that Conrad wrote about what he knew and what he knew was the world of men, just as Jane Austen writes best about women for similar reasons. I also have to disagree with you about women not being central to any moral problem. Marlow's lie, when he tells Kurtz's 'intended' that K's last words were 'your name', is precisely at the centre of the novel's wider point about the heart of darkness and the corruption that permeates western societies: here it is, even in the most personal, the most private of transactions. Kurtz's report is another example: a finely composed and carefully expressed official report with Kurtz's own savage thoughts scrawled upon it.

Now whether Marlow feels he needs to lie to her because she is a woman and therefore can't handle the truth is another matter, but the implication is that he regrets the lie even though he knows it was necessary. The whole edifice, from government, business, to the relationships between men and women, is, in Conrad's world, built on lies.

MG: But the 'intended' being a woman is still not morally involved in the story in my view, she is rather deliberately removed from such involvement. No choice is given to her, not I think because she is considered too weak as a woman to receive the truth (she probably instinctively recognised 'the lie' anyway, if she 'knew in her heart' her man!). It is the man again taking the moral decision to tell what is a kind and compassionate lie on this occasion, creating maybe a dilemma for Marlow in being forced at this moment to recognise good as well as bad lies. Or perhaps, if it hadn't happened to Marlow before, he is simply now faced with the totally demoralising fact that life and lies go together, good or bad - heart of darkness indeed. All open to conjecture, I feel, which is fascinating.

CR: Oh, yes, that's true, she is definitely remote from the 'centre' of the story, but the story is about men; it is the inability of men and women to 'only connect' as Forster puts it that Conrad is getting at. What he's doing I think is exploring man's (and I mean man's, not woman's in this context) tragedy: that despite having agency, he lacks power. More specifically he lacks power over his own existence; he cannot acknowledge his emotional life, cannot engage directly with others, must behave amorally as a matter of survival. This is one of the great revelations of Modernism, that modernity demands such heroism and sacrifice but offers no compensation. I'm thinking of Hemingway's Jake Barnes, Gabriel in 'The Dead', or Woolf's Mr Ramsey (and all those war dead Woolf has hovering in a circle behind her as she writes); in its popular incarnation this model of tragic manhood even extends to Superman and the impossibility of revealing himself as Clark Kent to 'connect' with Lois Lane. Without these explorations of manhood I don't think feminism as we know it could have been possible; the nineteenth century novel contains plenty of feisty, strong women, but the social structures are rigid, unchanging, and (mostly) unchallenged. Jane Eyre gains some level of equality with Rochester, but only when he is maimed; in marrying she becomes his possession. Even Dickens fails in this regard: Oliver Twist turns out to be upper middle class, which explains why he is able to resist descending into moral turpitude. Modernism overturns all this and offers up the horror of it all so that we can choose to do something about it.

MG: Wow, 'having agency but lacking power' and all the rest you say in the following sentence sent shivers down my spine.

But I don't think it is Modernism that came up with these ideas. I helped on my son's thesis looking at male heroism 'From Homer to Hemingway' - not quite into Modernism perhaps? - as far as the aspiration to heroism is concerned, which I link aspirationally with all forms of male creativity in the arts or sciences. Homer also sees no compensation at the end of the sacrifice in his sensitive examination of the destruction of youthful and creative souls in war. There are two sentences in the Illiad and For Whom the Bell Tolls which make a strong initial impact on the reader in terms of the futility of war "Then Ais Telamonius knocked down Simoisius, the son of Anthemion, in the full bloom of youth" followed later by the huge impact (no compensation) to be felt by the father Phaenops on the death of his two sons Xanthus and Thoon killed by Diomedes which compares in FWTBT with the death of the boy from Navarra "The boy from Tafalla in Navarra, twenty-one years old, unmarried, and the son of a blacksmith" given a family face only when Jordan reads the poignant personal letters from sister and fiancee found on the boy's body. I suppose it's just that the Illiad seems such a long way off but in terms of human history, heroism and useless sacrifice it could be yesterday, as I see it. As my son wrote "The language of Homer and Hemingway pulls the reader in without ambivalence. We sense the full pathos and tragedy of young lives cut off in their prime and the implications of their deaths that open up the deepest questions about the value of human existence and its meaning."

I wish we could choose to do something about it (the horror of it all), men and women both! Maybe Conrad wished that too?

Posted by Chris Routledge

Share

Related Articles

World Book Day® and The Reader celebrate the fun of reading

National reading charity World Book Day is partnering with Shared Reading charity The Reader for a fun-filled day in…

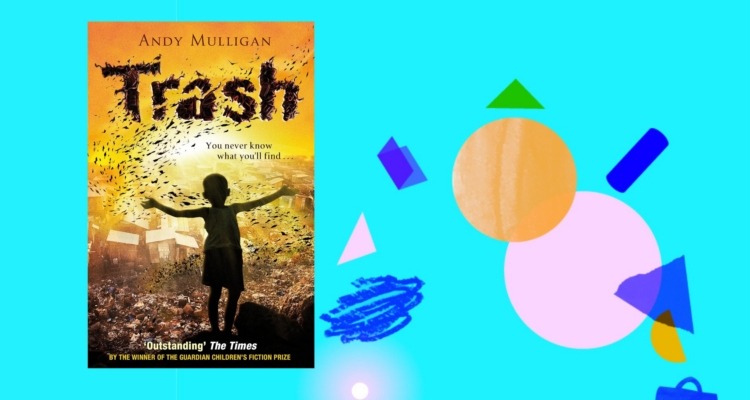

February’s Title Pick for Children: Trash by Andy Mulligan

Through our Bookshelf this year we are exploring the different places that people call home. From the very beginning…

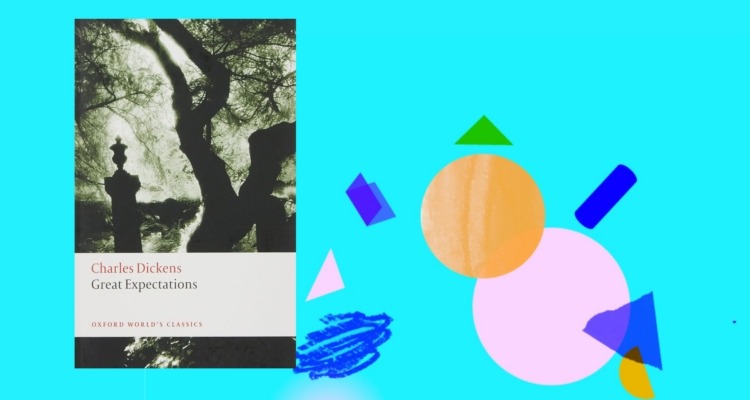

February’s Title Pick for Adults: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

Great Expectations by Charles Dickens The Reader’s staff and volunteers have been leading Shared Reading groups in many different…