In Care, Into Reading: How can we improve the lives of young people in care?

Published last month, In Care, Out of Trouble reports a worrying correlation between children in care and in custody, begging the question, how can we improve the lives of young people in care?

It is in all of our interests that as many children as possible are enabled to grow up to become successful, law abiding and fulfilled citizens well able to be good role models for the next generation. - In Care, Out of Trouble Report

The In Care, Out of Trouble review for the Prison Reform Trust also found that half of children in youth custody came from foster or residential care. Lord Laming suggested that this was in part due to the police being called on to deal with challenging behaviour that would otherwise have been resolved by parents.

A week previously, David Cameron also introduced the care leavers' covenant, pledging that those leaving care would be given "far more effective support", including a mentor for everyone under the age of 25.

Building networks of support is crucial to improving the lives of young people in care, as is championing education but, as The Reader has found through its work with Looked After Children, helping children and young people to develop confidence and a greater sense of self is key.

"Investing in childhood is more than a nice thing to do. It has a real value that goes beyond the child as it facilitates the future well being of society." - In Care, Out of Trouble report

The Reader's Shared Reading projects promote Reading for Pleasure, creating an enjoyable and social experience centred around literature in a safe and welcoming environment. For children and young people in care this can mean specially tailored one-to-one reading sessions, often in the home, that deliver the individual attention they need dependent on reading level, attitude and behaviour.

Working directly with families in Liverpool, the Off The Page project aims to improve the lives of disadvantaged children across the city through one-to-one Shared Reading experiences. Now nearing the end of it's first year, Off The Page have hosted a five day summer school, several family fun days and established 70 regular one-to-one reading sessions led by volunteers, directly engaging children to promote a love of reading for pleasure but also extending to the adults in their lives - be they parents, carers, family support workers, community staff and volunteers.

Desi's Reader Story:

"Desi" is a 13 year old looked after child who came to The Reader through an event at Calderstones Mansion House. Desi has some attention and behavioural problems and could be difficult to engage during reading sessions.

"It felt like a constant battle to keep Desi entertained and engaged. We imposed structures whereby we had volunteers with him the entire time. A few of our fabulous volunteers were a dab hand at this, particularly one lady, Marie. Marie is disabled and has a calm, kind yet assertive way about her. She was a constant caring and patient presence even when Desi was at his worst and she got him to help her with her walking sticks and wheelchair which he accommodated willingly." - Volunteer Coordinator

When this programme of events came to an end and consideration was given to pairing the young people involved with volunteers for continued one-to-one reading sessions, Marie was the ideal candidate for Desi.

Despite initial efforts to visit Desi proving difficult Marie and the Volunteer Coordinator persevered.

"We learned from his carer that Desi had frequently been in trouble at school for hitting, spitting, running off, and that he had a reading age of 5. I left feeling defeated, thinking there was no way we could persuade Desi to agree to the reading sessions.

We agreed to try again at Desi's school the following week. The night before I worried about him, about how difficult he could be but I knew we couldn't give up on him because... I get the impression that a lot of people have given up on him before.

When Marie and I met with Desi and his teacher we told him that Marie had chosen to volunteer her time to read with him, a big grin emerged across his face. Marie told him that she loved his sense of humour and his big smile - he hid his face behind his hands, he doesn't know what to do with praise.

We told his teacher about the events he'd attened at The Reader, she was amazed by all the positive things we had to say about him. His teacher wondered whether we were talking about the same child - again, Desi hid behind his hands." - Volunteer Coordinator

Marie's Volunteer Story:

Marie met Desi during the event at Calderstones, she knew he'd been challenging at times but was keen to continue reading one-to-one with him when the opportunity arose.

"One of the ways we were managing his behaviour was by giving him some responsibility. I have a wheelchair to go long-distance and we made Desi the monitor, he had to mind my walking sticks and fold them up for me. I told him 'There's only you that can do this, nobody else is allowed', I think it made him feel special, giving him that task."

Marie reads with Desi at his school where there is support from onsite professionals who can help to manage him (Desi can sometimes be confrontational or even aggressive). Because Desi needed to fiddle with things during the reading sessions, Marie initially brought him some Play-doh to keep his hands busy but since then Desi has asked her not to bring it anymore, telling her "I don't need that now".

"Desi is thirteen but has a reading age of five. We began by reading picture books with small amounts of text he can manage, he's a very visual kid and the pictures spark his interest. The stories needed to be short because Desi can't sustain his attention for anything longer. After a long time we moved onto the A Little Aloud anthology and because there were no illustrations I gave Desi a pad of post-it notes to draw on while he's reading, it helps calm him physically.

We've moved him on from reading very simple texts that accompany pictures to texts that don't have any illustrations, that's real progress, he reads longer stories, his attention span can last sometimes for twenty minutes in a story that really grabs him. He'll settle for longer and he'll settle quicker."

Marie has been surprised by Desi's insights during the reading sessions and has found that volunteering has been a learning experience for her too:

"Because he's such a visual person, Desi is absolutely superb at recognising characters' emotions. When we read Shaun Tan's The Red Tree, we spoke about the illustrations, about why the character's face didn't have any features. Desi knew she was sad: 'they've drawn her head slightly tilted down, that's what people do when they're sad'.

I'm not a visual person, for me it's always been about the text so I was genuinely learning things from Desi, not just eliciting his response.

He'll very quickly draw a shutter down if you ask him about himself. He's much happier talking about me or about the characters in the book."

For many children and young people in care, the closeness of sitting with an adult while reading, and the individual attention involved in such a simple act, offers the greatest sense of value. Volunteers have reported how little subtleties, such as making eye contact and mirroring your facial expression can often be a sign of huge progress for children who have never experienced bedtime stories growing up.

Marie calls this "a void" for the children in care that she's worked with, something paramount to childhood development that these one-to-one reading sessions can begin to repair. She says of the experience: "That was missing from that child's life, and now it's there."

"Okay, you don't change the world because you sit there with them for half an hour on a Tuesday morning, but they don't see books as the enemy anymore, they don't see them as boring, they don't see them as something that have nothing to do with them. Reading experiences have very long fingers and they stretch very far into the future.

I remember when I started reading with Desi, he wasn't familiar with handling books, didn't know where to find the page numbers but now he's so curious about them, about what price they are, what the barcodes and ISBN numbers mean. We got a whole new bag of books in the Off the Page Membership Pack and began with a little stock take - Desi handled the books, looked them all over, what's it called, who it's by, how much it cost, how much the whole bag of books cost: "I bet there's more than £100 in there!" he'd said, and I think the meaning he takes from the combined value of all those books is that he is valued.

You can see him physically change - his head lifts, his shoulders go back, you see the pride in him and just a little grin, you know, 'Somebody cares about me enough to give me over £100 worth of books, and they're my books."

And if you want to know if the intervention has developed his literacy or made educational gains for him? When we began reading, Desi really struggled, but now, we've read 14 books together, they might be simple books, he might still need some help but that's a real sense of achievement for him, we keep a reading log of how many books he's read, so he can see the progress he's making.

That's not really what The Reader's model of Shared Reading is about but it's part of what

happens when you give a neglected young man an opportunity - an opportunity he's not previously had - to read, which I think should be a valuable and wonderfully rich experience that every human being should be exposed to. Just reading for pleasure, no demands, no comprehension exercise, just something for fun. That's what makes it worthwhile, he's had that experience now.

Kids like Desi are never ever future-based they don't look further than the next ten seconds, but this has introduced a new way of thinking for him, it's given him an idea of what he can achieve, how many books he could read in the next one or two or six months. He gets a little glow from that."

Marie has witnessed firsthand what an impact these kind of interventions can have with children and young people in care. For a child in care, reading for pleasure, rather than to improve literacy, helps to develop new interests, to break down barriers and ultimately, to provide the building blocks from which they can build new foundations.

"It's about helping them to build new parts of their identities, to be defined by more than just the paperwork in their folders.

Desi may never be a real bookworm but he's a young man who can say "I've read 14 books in the last three months" and that begins to sow the seeds for new identities - "I'm a reader, I am somebody who has books in my life" - and those are the kind of profound shifts that make a difference in the long-term. He's a remarkable young man."

As Marie notes, not every child Off the Page engages with will become a book lover or a lifelong reader, but the project's aims extend further than that. By breaking down barriers with literature now, The Reader leaves the door ajar for those children to return to reading in the future. Books will no longer be 'otherly' to these children but something open to them if and when they choose to seek them out.

The Off the Page project has also helped to build essential social experiences for the children and young people engaged, creating positive interactions built on a shared experience, as well as providing opportunities for relaxed, open and honest discussion that centres around a text and depends entirely on how much or little the child is comfortable sharing.

“Daisy”, aged 10:“I wish I could read with Joyce forever ‘til one million or a billion or a gazillion infinity number…I feel so happy when I read with Joyce because then it makes me take all the bad memories and think about the good ones.”

“The teachers started to get fed up of me…they said to me at the start of the year, they said ‘You’re not gonna be allowed a place at our sixth form, you’re gonna have to go elsewhere.’About two weeks ago I found out I was allowed a place in my sixth form. They were like “You’ve transformed into a whole different teenager, you’re just so much more calmer and patient and getting into school and doing what you’re meant to do’ and I was like ‘I know’.

Share

Related Articles

Storybarn Book of the Month: Saving the Butterfly

This month, as part of Refugee Week (16-22 June), we've been taking a look back at one of our favourites…

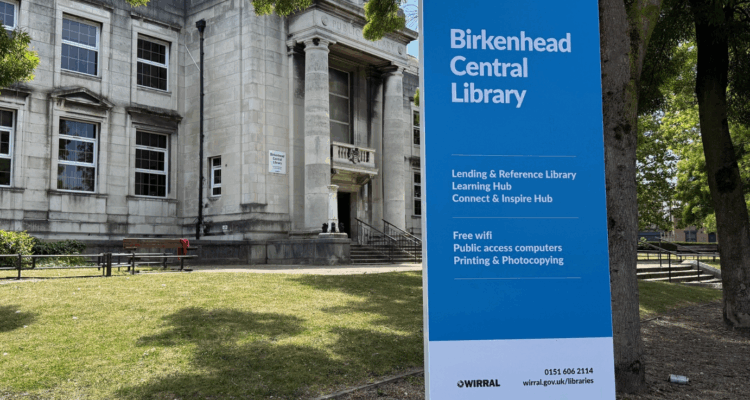

Shared Reading in Wirral Libraries: ‘As a kid people read stories to you but as an adult you lose that – and it’s a fantastic thing to do!’

Two Strategic Librarians for Wirral Libraries, Kathleen McKean and Diane Mitchell have been working in partnership with the UK’s largest…

Pat: ‘You don’t need to be an academic – it’s about going on your gut feeling about a story or poem’

National charity The Reader runs two popular weekly 90-minute Shared Reading group at one of the UK’s most innovative libraries,…