Reader Revisited: An Interview with Mark Rylance, actor and writer of ‘I Am Shakespeare’

We're taking a trip down memory lane and revisiting articles from The Reader Magazine. This article first appeared in issue 29.

Emeritus Professor Philip Davis interviewed Mark Rylance during the Liverpool leg of the tour of I Am Shakespeare. Written by Rylance himself, the play is a quirky and often comic celebration of the question ‘Who wrote the works of William Shakespeare?’ ‘The majority of people agree that it was the actor from Stratford’, writes Rylance in his programme note, ‘But also, the majority of people have not looked very closely into the history. For many years, some people have doubted, from what we know of the actor’s life, that he would have been able to write the plays and poems, and may therefore have served as a “front” for a hidden author, or collaborated more extensively than we imagine. I have been surprised again and again by the strength of emotion this historical question of identity raises. An understanding of the creation could reveal a creative process most beneficial to modern drama and society as a whole.’

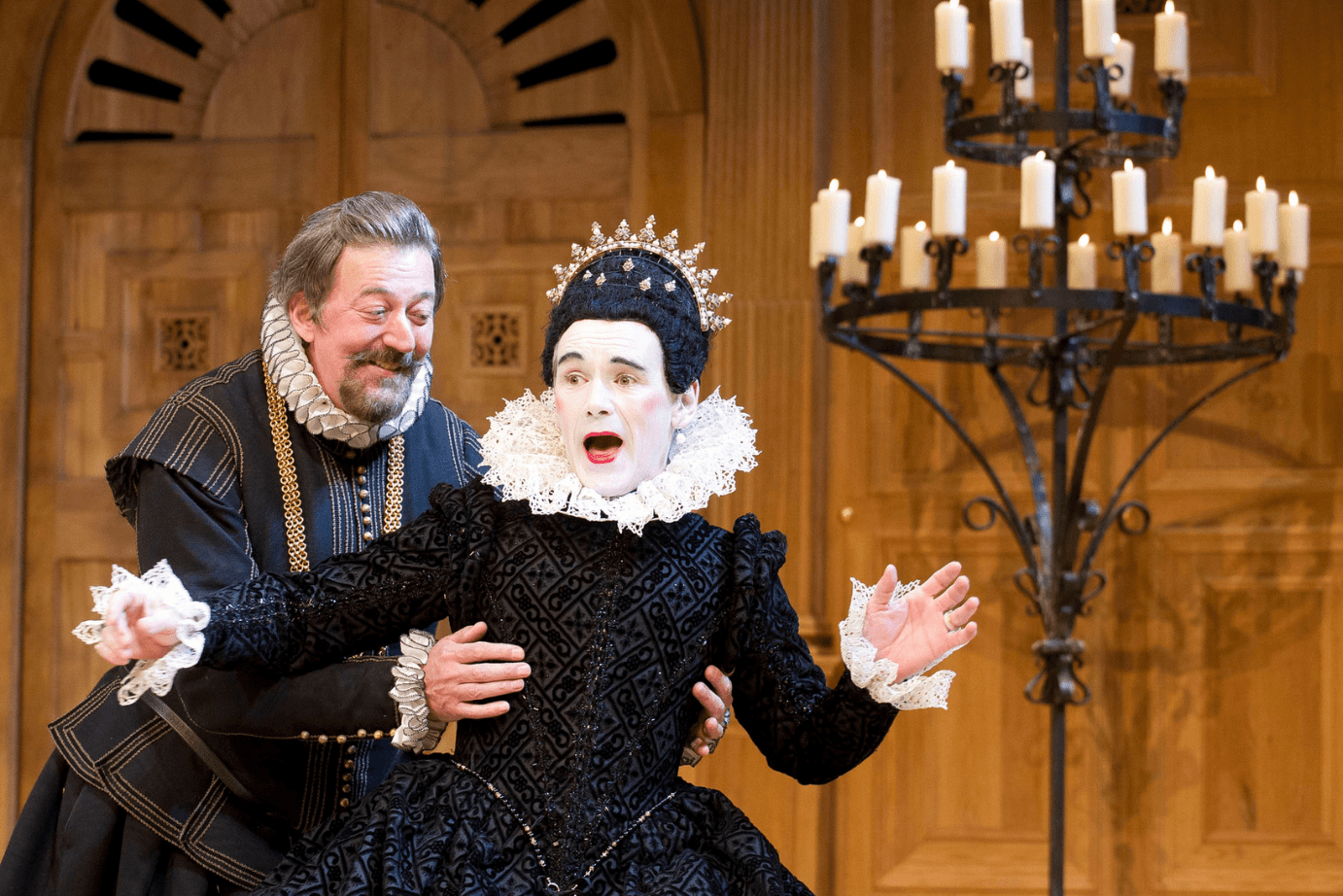

Stephen Fry as Malvolio and Mark Rylance as Olivia in 'Twelfth Night'

You are a great and an authentically strange actor. Bacon's line in the play seems characteristic: 'I love secrets, codes, and masks.' Would you say this area of anonymity and identity is important in what you're like as an actor?

I love secrets, codes, and masks. Bacon is the candidate for Shakespeare in I Am Shakespeare that I love the most – he's the one I have to be careful I don't favour in the play. I admire the other candidates too but he is the one who's helped me the most and he clearly loved those secrets and codes.

Are there times when as an actor you are trying to get into a Shakespeare play, when you feel you need a sense of cracking the code in order to do it?

I think there is a joy of doing a Shakespeare play – probably of researching one as well – but with the acting you have to go further than the academic does because you have to find out the cause, the emotional need to say something, which I suppose scholars will propose but they don't have to actually stand up and prove whether it works or not, whether it's believable to people, to the other actors and the audience. When playing a part like Hamlet over four hundred performances there is an ongoing discovery of layers of meaning in your understanding of what a scene or a line means, but also suddenly what's happening in the world can change the meaning. Hamlet says: 'The time is out of joint; Oh cursed spite, / That ever I was born to set it right.' You know what that means but then Tiananmen Square happens and you see a young man in front of a tank, and you suddenly have a considerably more powerful sense of meaning that young revolutionaries must have.

But there's a difference between the code and something contemporary that could help stimulate your imagination.

The code is something to do with really making decisions. If you're playing the Duke in Measure for Measure, for example, you have to decide at the end whether he is a manipulative bastard or a philanthropist. Is his speech to Claudio about the absolute of death a version of torture or a rather naff bit of advice, or is it that he wants young Claudio to be less reckless, and is therefore giving him a death experience? Those kinds of decisions are crucial, and take a number of code-breakings to come to the right one.

As with many considerable actors, there's something quite anonymous about you. Although I Am Shakespeare is concerned with identity, there are also parts of the play that suggest thoughts exist almost prior to people. I've seen you in Measure for Measure and there's a lot that comes at pace and feels improvised but crucially there isn't a stability of character. 'Be absolute for death', the Duke says, but at that moment it seems this is an idea that is called into being that needs to be thought by Claudio and has to be given somewhere. It's as if meanings are coming in and out of you, and I don't think you're worried about identity, put it to you, at all. [Mark laughs.] Don't laugh too long because I can't put that into the interview!

It's very funny. Maybe I'm not so scared of being called a crackpot as other people but in my own personal world I have a flexible identity. I take on other people's identities and I'm very greedy for them, for lots of different identities. I'm wary for some reason, like an animal would be wary of a zoo, of being pinned down as one particular identity.

I travelled back to my home town in Nottingham at one time to see you in Macbeth, and the actors told me afterwards that this is somebody who doesn't care what people will think and who will protect the group.

You know the funny thing is I forget. When I'm working on something like Macbeth, I absolutely forget how far out it is, how out of consciousness, and I am like a child. I just find it so fascinating, and then I remember to think if people are enjoying it and following the story, but I'm not thinking 'will they be offended?'. I'm always rather amazed when I realise that what I'm talking about is off the radar of most people.

I get the sense that your ability to move between different thoughts and identities isn't simply greed but is to do with quite archaic beliefs. Here is an example from the play, I Am Shakespeare, which I enjoy, but for the most part the play can't do for you all that you want it to do because the identity issue is split between 100 many people. But when your character is not quite involved in that whole area, of the club of the illegitimate, then the play becomes very strange for a moment – suddenly darker, and although the characters and the actors look very separate, what's really interesting about identity is how one person could be all of them and move between them. That one person in a way is the sort of person you are.

I think it's the sort of person Francis Bacon was too, in my impression of that period he had the ability to be Shakespeare...

What you're really doing is reinventing Shakespeare as Bacon - it's still the same thing, you want to be one person who can be many people!

I think I'd get more from 'Shakespeare' being a group actually, but I probably do have an interest in archaic beliefs. I'm interested in platonic type ideas and very interested in indigenous people's faith, and pagan faith, and I'm a practiser of those ideas. I believe that the laws of courtesy apply on this side of the veil and on the other side of the veil.

What do you mean by courtesy on the other side of the veil?

Places such as this building, The Playhouse, have ancestors who contributed enormous amounts of effort or money. Their collaborative effort created a spirit, this building has a spirit. You can see it has been a music hall. The many performers, stage hands, audiences, have had experiences here, and all that vitality has added to the place. There is a spirit that is left behind much as we leave the dust of our bodies around. So there are rules of courtesy or of thanks when you come into another person's space on both sides of the veil. Robert Bly, the American poet, said to me once - he said it to a group of men – ‘your depression is in direct proportion to your inability to praise’, and this has really stayed with me. I feel that those elemental spiritual things need to be acknowledged.

The thing that Shakespeare is very good at teaching is that we should be wary of hierarchical responses. In my acting especially, and now a little bit in my writing too, I feel more of a vessel than the sole creator. I have to do the necessary work, the reading and preparing, of course, and mulling and heating myself up in a certain way like you'd heat up a pot, but ideas are really gifts.

Can you explain that sense of above and below and say why Shakespeare would be interested in that?

From the work I've done on the comedies, particularly with the scholar Peter Dawkins at the Francis Bacon Research Trust, I've become convinced that the Tree of Life, the Kabbalistic Tree of Life is really the backbone structure of Shakespeare's comedies. The Tree of Life has those ten principles, archetypes, which are probably developed from the Egyptian into the Judaic system. In Much Ado About Nothing, for example, at the top of the tree, you've got Don John and Don Pedro – John the thinker and Pedro the speaker. One is the archetype of wisdom, love, and the other one is the archetype of intelligence, the reflective. Then you've got Beatrice with the perception of warlike Mars, 'Kill Claudio’. Below her, you've got Benedict, with mere thought and not a lot of perception –the Mercury position. So you've got Mercury, Mars, Saturn. And on the other side you've got Venus. Pedro is trying to bring Beatrice and Benedict together, while John is trying to separate them. You have these archetypal characters developed with great naturalism. What's above, the divine, is here in us too.

This is turning what would be static allegory into a sort of force field in which the spaces between apparently static things is where the drama comes into being.

That is the love of the code for me. But let me just finish your question. At the wedding scene when that huge terrible thing happens – when Hero is denounced on the brink of marriage by Claudio and by her own father – Friar Francis creates that clarifying space. Friar Francis comes in with enormous wisdom, way above everything else. But at the same time, at the bottom of the pile, you've got Dogberry, absolute chaos, chaos of language, chaos of understanding, and yet Dogberry is the one who finds the evidence that will clear Hero. Both figures are needed. There is a lot of low fun with that chaotic character down below, but at the same time Shakespeare gives him the key, the entrance, into the resolution of the mysteries. This makes the Stratford man very interesting because in a way he is Dogberry. The evidence about the Stratford man shows that he is the antithesis to the consciousness of the author you would expect to find behind his plays. What is most challenging to me is, if someone else wrote the play, such as Bacon, then what is the importance of this Stratford entrance point? It's kind of obvious I guess, I mean it makes a lot of people feel a lot better about themselves.

I like the idea of this somebody who is extraordinary pretending to be ordinary. I saw a matinee of Much Ado where you were opposite Janet McTeer. As Beatrice she was saying disparaging things about Benedict to you in disguise mode, and at one moment, with a shrug more than with the mouth, you say 'fair enough'. Now, I think, in theory, if an actor starts putting his own words in Shakespeare I'm very annoyed, but actually it seemed to come out of the body, and out of the atmosphere between you more than out of the character.

I do that quite a bit you know, little noises and shrugs and things. Other actors used to mock me in a friendly way at The Globe about it.

It seems to be a sort of response to the atmosphere rather than character driven. Your characters are quite inchoate and good for that reason. They're quite fluid. So in Macbeth you are the one actor who has convinced me that the spirits are actually there. When you talk about them they are more there than you are. Some speeches come from the character, and some speeches come from the object of the speech, and you're good at that.

I tend not to go in with a concept of a character now. I don't know if I even did before, certainly not by the time I was doing Hamlet. I was preparing extensive lists of everything the character had said about himself, everything he said about others, everything everyone else said about him, and then just solving lines and scenes and finding where that brought me rather than interpreting those lines and scenes. That may be why they seem quite fluid.

One of the technical things you do, which interests me a lot, is that sometimes you'll let a line just go all the way through and then wait, and have the audience wait for the meaning at the end. In I Am Shakespeare, for example, you're talking about Shakespeare as a plagiarist and you say: 'Italy, Italy, Italy, but you haven't been to Italy have you...' and there's no emphasis. You do that a lot in Shakespeare. It's as if you want to get past, to get over the speech, and then the speech happens afterwards. Are you conscious of that as a technique? What are you up to when you're doing that, do you think?

That's very perceptive of you. I'm hiding the fact that I'm planting it, I'm planting and hiding... It's about timing.

You get past the thing, and then you have to go back into it for a split second, so it's only a wobble.

Exactly, it's interesting because it happened just last week – the lines stopped getting a response, they weren't as amusing to the audience, and I realised that I was going straight to it, too straight, whereas if I was going to do something else, like put the map of Italy here, to pull attention off, the response would come back. I don't know why it is, but it makes a difference in how the line is planted well. It helps people to feel too that the play, the event, is not prescribed. I'm always trying to get the feeling that it is happening spontaneously.

And that is important with the Shakespeare, particularly, otherwise you get the authorised version.

Yes, yes, it's very important. His writing changes over the course of his writing career, the movement of full stops in the middle of lines and things and the verse changes too to be more like spontaneous speech.

'Matching cause', that was the phrase you used in the question and answer session after the play... You said that there's always a matching cause because art is based on obstacles and if something great happens it is because of a blockage elsewhere. This balancing act seems to be part of your sense of the structure of things. So to challenge you – what is your own matching cause?

I think there are a number of matching causes really. I wasn't able to be understood until I was about six. I could speak but I don't think I used consonants at all – I can't quite remember why I wasn't understood but my brother was the only one who could understand me. I was sent to speech therapists. So very early on I had the impression that it was difficult for me to communicate with other people. I was also intensely shy and self-conscious as a younger person – I'm better now because I have an identity as an actor, but even before I was nine or eight I was playing parts, and maybe that helped me to find language and words, copying people who were in stories or on television. That world of pretending to be someone else always had more liberation, more chance for expression, for experiencing things, than the real world, so to speak.

Do you think the vulnerability has moved into your capacity to be surprised by the outside world?

Maybe so. I get a great buzz from being with a group of people but I need to have a task and a play. I think it's that obstacle of feeling a little self-conscious or outside of groups in real life. That obstacle prepares me for the theatre where I love the interaction. The stage and the interaction seems real and intimate.

'Where do people exist who do not exist?'

Very good, yes. That's Mathew's favourite line in the theatre. Well I feel that sometimes, a kind of weird feeling like that.

Where does religious happen for you? You clearly have a whole world view that you work within.

I am a pantheist I suppose.

And an eclectic. You put a lot of things together in that whole. But say a bit more about the pantheism.

I live my life as fully as I can, I mean, I'm not so sure that our consciousness as human beings is the greatest consciousness – it can be destructive and it's capable of such cruelty and blinkeredness. The soul of the animal and the soul of the world is something which can be appreciated and it may be helpful to our society. That's something that Shakespeare does, he ensouls people, he ensouls things, and that is one of the reasons Shakespeare plays are good to do. He ensouls people almost unconsciously. I don't really practise a religion. I have a faith, and I have a spiritual practice, but I don't care for religion really.

My faith in the simplest sense is that there is a force of love. There is a collective consciousness that is beyond my conception, and there are different levels of that consciousness, but it is a consciousness that one can work with and that one has in different degrees. I think there is a rhythm to that energy and that it is something to do with timing and the working of the year, and I think that a lot of those folk festivals, or Celtic festivals, a lot of these things that were crushed by the Civil War and the industrial revolution were a great loss to this culture, and I search for them in other cultures.

The rhythm of getting a line right, is that also part of that greater rhythm?

Oh yes. Those crop circles that happen overnight are part of it too. I suppose I think of it in terms of everything is in another consciousness at work in our midst.

What does it want to do? Or perhaps the question is what does it want us to do?

Well that's a really fascinating question. I think it wants us to think outside ourselves. There are often patterns in the ideas that we have, images that are in our consciousness. Geometric structures that are unfamiliar, DNA type patterns, mind patterns, very interesting type communication from symbologies.

Shakespeare is one of the greatest understanders of those shapes and configurations, would you say? He seems to understand those charged spaces that come into being even if only intuitively half created by himself.

I think that the plays can do that. We're only just coming to understand the kind of energy, the force field that the plays create. One of the things people say about my enquiries into Shakespeare is that I deny his theory of genius. It's not true! I do think Shakespeare is a genius, a very inspired genius in a strong line of inspired geniuses that share a court of the muse which really exists and which can be sourced by a particular type of human being. This ability to access it is probably to do with the genes and physical makeup of that person, or maybe to do with the society that person has been born into and the circumstances of their life.

I've got one last question. Post-Globe, what is your mission?

To make new works. I want to make new works of theatre with what I've learned. I've given twenty-five years of my life to predominately exploring this Elizabethan period, and now I want to make new works.

At the risk of embarrassing you, I need to say to you that there are people who one doesn't know you are glad are in the world, and for me you are one of those.

Thank you so much. Your questions have been so perceptive, I mean I've talked very openly with you about stuff I would normally mask and veil.

Share

Related Articles

World Book Day® and The Reader celebrate the fun of reading

National reading charity World Book Day is partnering with Shared Reading charity The Reader for a fun-filled day in…

February’s Title Pick for Children: Trash by Andy Mulligan

Through our Bookshelf this year we are exploring the different places that people call home. From the very beginning…

February’s Title Pick for Adults: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

Great Expectations by Charles Dickens The Reader’s staff and volunteers have been leading Shared Reading groups in many different…