Reader Revisited: Jane Davis in Conversation with Jeanette Winterson

We're taking a trip down memory lane and revisiting articles from The Reader Magazine. This article first appeared in issue 44.

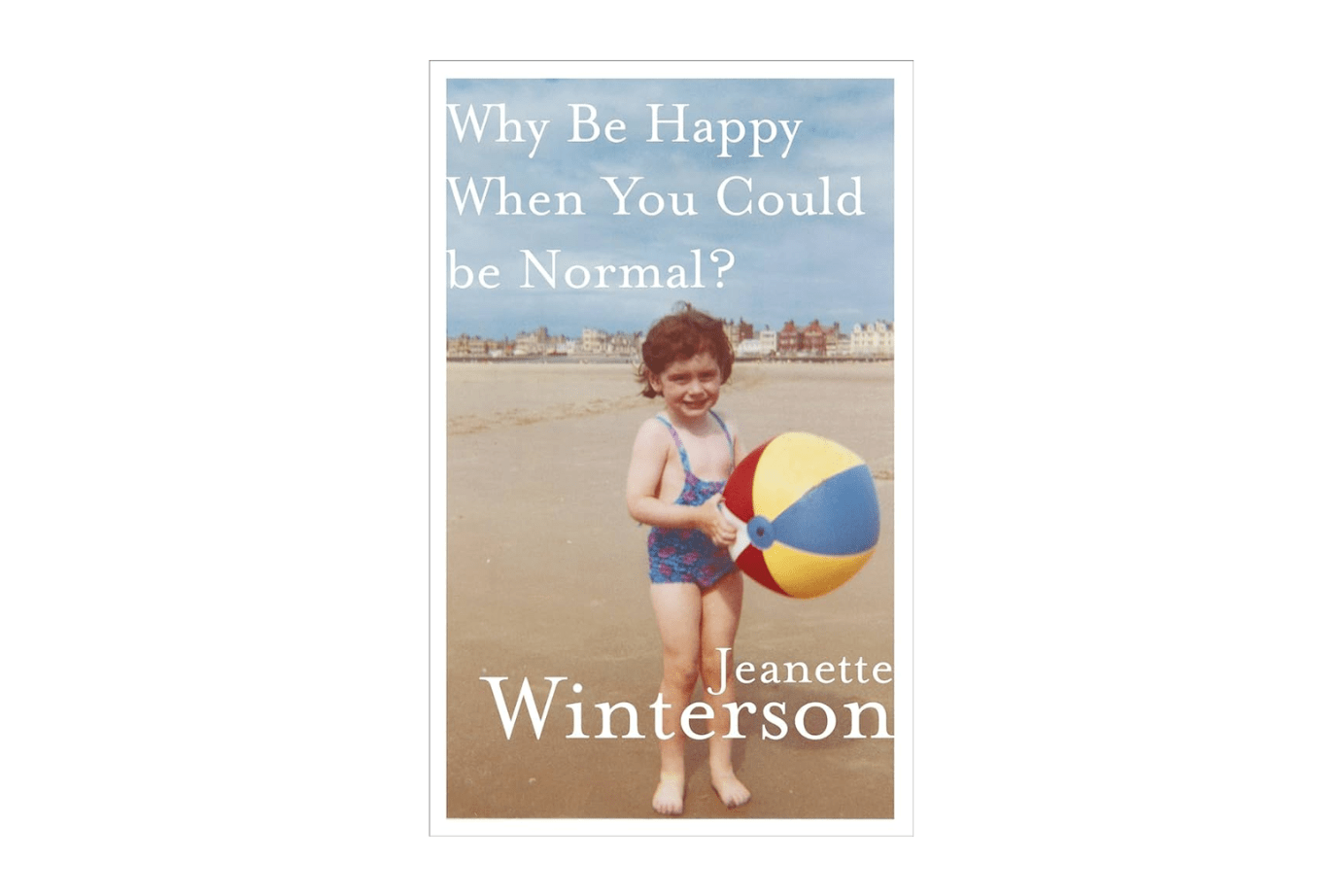

Jeanette Winterson's memoir, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? relates the story of her suicidal breakdown and subsequent search for the truth about her birth mother. It is also an account of a life shaped and given the deepest of meanings by books. As with Jeanette's favourite Shakespeare play, The Winter's Tale, the book falls into two halves separated by a wide and untold gap of time. The opening chapters detail the reality of the life that gave rise to Winterson's stunning first novel, Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit. Then, following a short intermission, the book flashes forward twenty-five years to 2007, when Jeanette accidentally uncovers her own adoption papers, and begins the painful and testing process of discovering her origins.

Jane Davis met Jeanette in Manchester for a conversation about the book in October 2011. What follows is an edited transcription interspersed with extracts from the book.

JW: The trouble is everything takes a lifetime, which I think is the best argument for something of us continuing after death. Surely you can't just work a thing out and then stop it? Nature doesn't do waste, does she?

My time was up. That was the strongest feeling I had. The person who had left home at sixteen and blasted through all the walls in her way, and been fearless, and not looked back, and who was well known as a writer, controversially so (she's brilliant, she's rubbish), and who had made money, made her way, been a good friend, a volatile and difficult lover, who had had a couple of minor breakdowns and a psychotic period, but had always been able to pull it back, to get on and go forward; that Jeanette Winterson person was done.

In February 2008 I tried to end my life. My cat was in the garage with me. I did not know that when I sealed the doors and turned on the engine. My cat was scratching my face, scratching my face, scratching my face.

(from Why Be Happy When You Can Be Normal?)

JD: Tell me about your cat.

JW: Spikey. He's more like a dog. I've got two cats, Spikey and Silver, and they're my personality chopped in half. One of them is really outgoing, loves me and loves visitors, and the other goes 'Oh my God, not another person, please!' That's totally me in the cats. It was incredible that the cat was in there because without him I wouldn't be talking to you. The attempt would have worked, no question. He hates me going away. He sleeps on the bed and sits in my study and works with me. He looks out for me. You know in the fairy stories there's always an animal helper - that's what I got. Just at the minute when there was nothing else, and your brain can't save you, and your friends can't save you, and certainly you can't save yourself, there's the animal helper.

JD: You've written a profoundly religious book. [JW looks aghast] In the sense that the whole story is a story of love

JW: I am sure that love is the highest value, I do believe that: it is the only thing you can set against the devouring principle, which rules so much else in our lives. We have to eat to live and that becomes its most grotesque with consumerism and the raiding of the planet that we do. We've never got a balance with our devouring instincts and I think the only thing that we do set against it is love acting as a check to say 'No, I won't take this, I won't eat this, I won't have this. I will give to this instead'.

JD: I have the feeling that the garage was a kind of rebirth or transformation. You use the word 'done' – 'My time was up... that Jeanette Winterson person was done'.

JW: Yes. It's odd those things stacked in the word. Done in, done over, done for.

JD: I also thought it meant 'completed' - something is fixed. Ok, your friends and relations might laugh and say 'Nah, still the same old same old' but...

JW: Oh yes, it is fixed and people who have known me for a very long time do say 'Yes, something enormous did shift'. Of course, the same old stuff goes on, but I know I'll never end up in the garage again. It's completely clear in my mind – I will die of natural causes or from something out there in the crazy world, but it won't be anything to do with me. That is 'done'. This now feels like a whole new chance and another set of things to get on with. I don't know where it'll take me but things have changed for me.

I feel much more open, both forgiving of others and forgiving of myself, of how I used to be. There are points in your life where you can see 'I needed that then’. I would never have escaped Accrington if I hadn't been full of a sort of Protean energy and I was ruthless. I thought 'I'm not staying; you're not crushing me. I'm going'. I had to have enormous energy and self-belief to do that. But what's interesting is that then life will still offer you another challenge, that you're not done. That was a big shock.

JD: I love the way you leave out those twenty-five years. Good! That's fine. Who the hell could bear to go through all that again?

JW: I didn't want the book to be that kind of story. What interests me is that in our lives things don't lie side-by-side chronologically. They lie side-by-side in terms of their emotional effect, their weight, and what they mean to us. It's not to do with the calendar in any straightforward way. I wanted to show that in the book. It's a memoir but its also a story and this story is, amongst other things, about the overwhelming absence of one mother and the overwhelming presence of another. The bit in the middle, those twenty five years aren't relevant to this story. So I thought, why can't I leave it out? I think that was right because what we want to know is where we go from there. The missing part is really the outworking of where I got to. I got there and I won some grace and I won some time, and went off and I did something with my life.

JD: And then it all ends up in a garage.

JW: It all ends up in the garage! And with no choice because - you don't chose it. You think from time to time, I could do this, and I think that is quite freeing. I don't think suicide or contemplating suicide is necessarily negative. Depending on the kind of person you are, you need to know that it's an option. I did. And that was useful for a while because I think the thought stopped it from happening but then there's a point when you're not thinking any more, and the psychic pain and the emotional pain is so overwhelming that - well, you're not thinking, you're simply trying to exit. It isn't rational. And no matter how smart you are, no matter how cared for you are - you know, I wasn't somebody with no friends - there's a moment where you cannot do it any more. I had to arrive there but by some good grace I was able to get through it.

There are so many fairy stories - you know them - where the hero in a hopeless situation makes a deal with a sinister creature and obtains what is needed - and it is needed - to go on with the journey. Later, when the princess is won, the dragon defeated, the treasure stored, the castle decorated, out comes the sinister creature and makes off with the new baby, or turns it into a cat, or - like the thirteenth fairy nobody invited to the party - offers a poisonous gift that kills happiness.

This misshapen creature with its supernatural strength needs to be invited home - but on the right terms.

(Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?)

JD: Could you tell me about 'the creature'?

JW: Oh yes, me and my creature. I was wandering about and we were shouting at each other. It was good to split the creature off. In technical terms I was crazy because I was talking to a split-off manifestation of myself that seemed real. As far as I was concerned, it was real, so it was a psychotic episode. But I think R. D. Laing's right about that - you sometimes have to ha psychotic episodes and not drug them into oblivion, and not l so scared that you can't go through them. It is a huge risk but you have to take the risk because if you do medicate it or you fail it in any way it's almost certain that it will kill you in the end.

JD: A lot of people give up at that point. They don't want to talk to the creature. They want to say, there is no creature. That kills you.

JW: It does. Either you become a Stepford wife or it'll kill you. That's the alternative. And I think our world gets in the way of people going through the process. There's no space for it, and everyone's terrified of it, and that's why they thrust the pills at it. That's why I didn't go to the doctor. I felt I've got no chance if I walk in that surgery; it's going to be on my records. I was certainly lucid enough to work that out.

Occasionally the creature appeared when I was reading, to mock me, to hurt me, but now I could ask her to leave until our meeting the following day and, miraculously, she did…

A few months later we were having our afternoon walk when I said something about how nobody had cuddled us when we were little. I said ‘us’ not ‘you’. She held my hand. She had never done that before; mainly she walked behind shooting her sentences.

We both sat down and cried.

I said, ‘We will learn how to love.’

(Why Be Happy When You Could be Normal?)

[Following this breakthrough, and supported by the loving relationship she created with Susie Orbach, Jeanette began the long-avoided search for her birth mother.]

JD: I cried from about page 170 onwards and I cried most at the point where you are finding out what your original birth certificate says, finding out who you are…. You say 'Susie held me'. Would any of this have happened without your partner, Susie?

JW: No, I would have lost heart, I wouldn't have been able to nerve myself up to it because there are so many hurdles. At some point I would have thought, I can't do this.

JD: You write 'She's smiling at me as the meeting begins and saying nothing, holding me in her mind. I could feel that very clearly'. So that's where I began to cry, because I suppose all of this last bit is connected to you finally being a baby and letting that baby be loved… The moment where you are given the piece of paper with the names on it and you describe them as like runes... It's hard to read, so painful. It's the name of your birth mother and your original name: 'I am standing up. I can't breathe. Is this it then? They're both smiling at me as I take the paper over to the window'. At that point, that's where I was in floods of tears. It felt like a birth. It felt like being present at a birth.

JW: It's true. I suppose they were both the midwives.

On the train home Susie and I open half a bottle of Jim Beam bourbon. 'Affect regulation, she says, and, as always with Susie, 'How are you feeling?'

In the economy of the body, the limbic highway takes precedence over the neural pathways. We were designed and built to feel, and there is no thought, no state of mind, that is not also a feeling state.

Nobody can feel too much, though many of us work very hard at feeling too little.

Feeling is frightening.

Well, I find it so.

The train was quiet in the exhausted way of late-home commuters. Susie was sitting opposite me, reading her feet wrapped around mine under the table. I keep running a Thomas Hardy poem through my head:

Never to bid good-bye

Or lip me the softest call,

Or utter a wish for a word, while I

Saw morning harden upon the wall,

Unmoved, unknowing

That your great going

Had place that moment, and altered all.

It was a poem I had learned after Deborah left me, but the 'great going’ had already happened at six weeks old.

The poem finds the word that finds the feeling.

(Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?)

JD: There's a terrible bit at the end of the book where you say ‘The baby knows' - about the loss of mother, everything, the adoption.

JW: Yes, I think the baby knows. You know that something has gone very wrong. I wonder, and I don't know about this, but I wonder if that absolute change for the baby prompts language early because that bit of your brain has to develop. You're desperate to understand what's going on around you. What am I going to do? I was talking about it to A. M. Homes in New York last week - I love her work. She wrote a memoir about her own situation called The Mistress's Daughter. Her father had a baby with another woman and that was her, and she was adopted. She thinks that when you do your search later it activates all this stuff which is in fact DNA material. She thinks it releases a chemical change because you've had to store this feeling or information. I asked her was she very precocious with language? And she said yes she was. You're seeking some explanation for why you suddenly land in this place with all the wrong smells and the wrong person, so it may be so. We're evolved to survive aren't we?

JD: I just wonder whether, before we're born, whether we have some kind of consciousness of where we are even though we're not here yet.

JW: I think we do.

JD: Wordsworth says our birth is a sleep and a forgetting. If our death is something like that, I feel very glad for you that you have had your thing in the garage and now this time afterwards. There's a real chance now for what happens in the second half to be freer, more creative.

The main thing I want to say is, you've been fantastically brave. It's a very brave book.

JW: Well, thank you.

Share

Related Articles

Storybarn Book of the Month: Saving the Butterfly

This month, as part of Refugee Week (16-22 June), we've been taking a look back at one of our favourites…

June’s Stories and Poems

This month we are celebrating the natural world, and especially the many wonderful creatures that live within it, with June’s…

April’s Monthly Stories and Poems

Our year of Wonder with The Reader Bookshelf 2024-25 is coming to a close – though we won’t be putting…