Reading Back #2: An Unknown Masterpiece

For the second in our Reading Back series we go back to Issue 14. Spring 2004. Philip Davis, now editor of The Reader, recommends Mrs Oliphant’s great novel Hester. Who reading the magazine back then could have imagined that the events of the book - a nineteenth century financial crisis, complete with greedy bankers and a run on the bank - could happen again, let alone just four years into the future? Suddenly, Hester is a novel absolutely for our times and for the moral and financial predicament in which we find ourselves.

(Hester is an Oxford World’s Classics paperback, edited by Philip Davis and Brian Nellist, and is available here at The Reader Bookshop.)

The Reader Recommends:

AN UNKNOWN MASTERPIECE

Margaret Oliphant, Hester

Philip Davis

Hester is a magnificent novel whose story and characters are guaranteed to keep the reader turning the pages from first to last. The principal character, Catherine Vernon, is what we would now call a career woman: an unmarried Victorian lady who has become chief executive of a bank, the family bank which she stepped in to save when her cousin John had brought it to the edge of ruin. He then absconded to France. At one time, it had looked as if she might have married this cousin, but he jilted her for a more beautiful young woman. From then on, the disillusioned Catherine has devoted her life to the bank, along with a host of poor and dependent relatives whom she houses and supports. We first meet this formidable Catherine when she is 65, and though she is beginning to take a back seat in the business of the bank, she remains the matriarchal centre of her provincial world and, indeed, the protagonist of Margaret Oliphant’s long-neglected novel of 1883.

So why isn’t this novel called Catherine and who is Hester? Hester is the fourteen-year-old daughter of cousin John. We first encounter her on her return from the family exile in France, her father now dead, her widowed mother seeking refuge in Catherine’s family charity. Hester doesn’t know the story of her father’s disgrace. A firebrand and a spitfire, she is already a proud and powerful young woman, determined to find something to do in the modern world. The one woman she knows who has really achieved something is, of course, Catherine. Although she admires her, Hester also resents Catherine, for her power and her control. Too alike to get on well together, they are like an older and younger version of each other. Anyone interested in the paradoxical love and hate, life and death conflicts of young and old will be absorbed in the deep psychological realism of Hester.

It is not called Catherine, because increasingly as the story develops, it is clear that the future of the modern world must lie with the younger people. But Hester herself is not the centre of the novel either, precisely because she is young and unformed – and because in this novel the character of the young is all too conventionally rebellious against the conventions of the old. Margaret Oliphant is expert at seeing both sides, in putting herself and her reader in the place of both characters almost simultaneously. The reader doesn’t quite know who to feel for most, because the author has thoroughly immersed us in life’s complexity. As one of the book’s older characters magnificently puts it: though ‘right and wrong, are like black and white’, the things that baffle us ‘are those that perhaps are not quite right but certainly are not wrong’.

The third major character in this novel is the young male relative to whom Catherine increasingly yields the running of the bank. Edward Vernon is the one person left whom she trusts, like the son she never had. He is her faith, her religion. And yet, secretly resentful of his benefactress, he threatens to repeat the old story of cousin John, by privately gambling his customers’ deposited money on the fortunes of the new Stock Exchange. It is Edward who drives the desperately compelling plot of this novel in a new modern world of money and of sex, combining as he does the pursuit of wealth with the pursuit of Hester herself. What happens virtually kills Catherine. In another story, in the happier parallel existence that shadows this book, Hester would have been Catherine’s daughter by cousin John – and that is partly why Catherine resents her.

‘No one will even mention me in the same breath with George Eliot,’ lamented Mrs Oliphant in Autobiography. But Hester should take its place beside the novels of George Eliot. In addition, it is the disguised and transmuted story of the author herself: a caustically rueful but determinedly powerful widow, left in debt by her artist-husband to bring up three children by the earning power of her pen. As a single parent, she felt she had perhaps sacrificed the quality of her work for the sake of her family. But worse, for all that sacrifice, her two boys still went wrong, just as Edward goes badly astray in the novel, leaving the mother wondering whether that too was partly her fault, through the very desire lovingly to protect them. In Hester, Margaret Oliphant turns round on her own motherly concerns, on her own powerful intelligence, and even on her own capacity for satiric bitterness. ‘Human nature may be easy to see through, but it is very hard to understand.’

Hester is bitter, pained, moving and sad, yet also often satirically funny and alive at the expense of its men; absorbingly exciting in story, profound in character and relationships. When you cannot find another novel by George Eliot or Elizabeth Gaskell, when you find yourself vainly wishing that the Brontës had written more, read Hester.

Share

Related Articles

We cannot just tell parents to read more. To truly improve children’s futures through reading, we need to properly support the adults around them to do so.

Responding to the Department of Education's announcement that 2026 will be a Year of Reading, The Reader's Managing Director Jemma…

Storybarn Book of the Month: Saving the Butterfly

This month, as part of Refugee Week (16-22 June), we've been taking a look back at one of our favourites…

Shared Reading in Wirral Libraries: ‘As a kid people read stories to you but as an adult you lose that – and it’s a fantastic thing to do!’

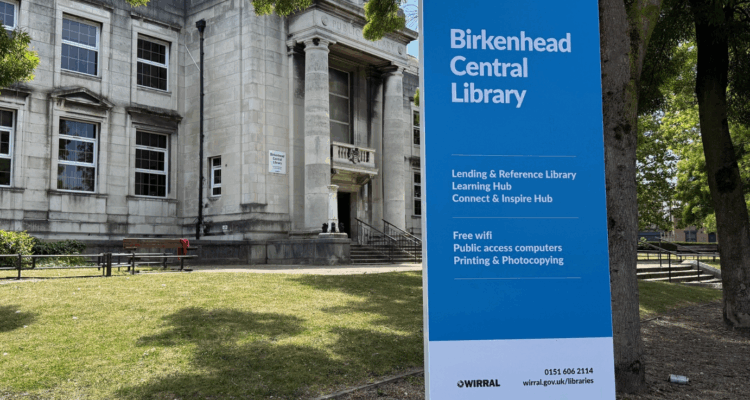

Two Strategic Librarians for Wirral Libraries, Kathleen McKean and Diane Mitchell have been working in partnership with the UK’s largest…