Reading Back #4: The Untold Truth (In Memory of Harry Patch)

Harry Patch, the last surviving soldier to have fought in the trenches of the Western Front in the First World War, died last weekend. His ancient, quavering voice, whispering warnings, will never be forgotten. Seven years ago, when Harry was a mere 103, issue 11 of The Reader magazine carried the following article. It seems appropriate to return to it for the fourth of our Reading Back series.

The Untold Truth:

Poetry of the First World War

Angela Macmillan

On March 4th 2002, The Times carried an article about the proposed construction of a road in Belgium which would desecrate six First World War cemeteries. Harry Patch, aged 103, one of the very last survivors of the Great War, had not spoken of it for eighty years, but felt so strongly that the dead should be left in peace that he broke silence to tell of the deaths of his three closest comrades during the Third Battle of Ypres: ‘A shell came over and burst among us. I was wounded, it killed my three mates, although I didn’t know it at the time. Nothing was found of them, they were simply blown to pieces... I’ve never forgotten them’.

More than 200,000 British Empire soldiers died on that Belgian stretch of the Western Front. 200,000 voices forever silenced, and Harry Patch representing just one of many survivors unwilling to speak the unspeakable. The disturbance of that memory prompted this old man to give voice to untold truths at last. His simple language, made eloquent by the gravity of its subject, outlines only bare facts. The rest remains in an eighty year silence.

Many of us, if we care to look back through our family history, will find we have grandfathers, great-grandfathers, great-uncles, someone, who took part in The Great War. If we are fortunate there will be some personal, written testimony in the form of diaries, letters or notebooks but these will rarely record more than day to day concerns – the weather, the food, the waiting about, the messages of love and hope. The awful reality was rarely communicated. What many of us now know of the soldier’s experience of war comes from the literature of the time and in particular from the poets. For when the terrible enormity of actual experience goes beyond the powers of human understanding, perhaps then the only adequate response is poetry. The best of the war poets, most of whom were already writing poetry before the war, realized that the function of poetry itself had to be reconsidered in the face of experience, as Wilfred Owen famously declared in the summer of 1918 in his Preface to a book never completed:

This book is not about heroes. English Poetry is not yet fit to speak of them. Nor is it about deeds, or lands, nor anything about glory, honour, might, majesty, dominion, or power, except War.

Above all I am not concerned with Poetry.

My subject is War and the pity of War.

The Poetry is in the pity.

Yet these elegies are to this generation in no sense consolatory. They may be to the next. All a poet can do today is warn. That is why the true Poets must be truthful.

Poetry now had to be a response to real experience rather than an aesthetic response to the muse or to abstract ideas. At Craiglockhart, the hospital for wounded minds, Owen began to find the means to express the very thing that was threatening to silence him. Taking war as his subject, he saw how the reality of suffering forces a new imperative in the use of language:

I have made fellowships –

Untold of happy lovers in old song.

For love is not the binding of fair lips

With the soft silk of eyes that look and long,By joy, whose ribbon slips, –

But wound with war’s hard wire whose stakes are strong;

Bound with the bandage of the arm that drips;

Knit in the webbing of the rifle-thong.

In the first five lines of this extract from ‘Apologia pro Poemate Meo’, poetic language aesthetically heightens the experience of love. But in the last three lines, in crucial reversal, it is the very experience of love that lends real significance to language of war – barbed wire, bandages, blood and guns, ultimately affirming and honouring the stronger bonds. In other words the poet does not go outside the experience in order to present it in purely poetic image or metaphor, but stays purposefully within it. This poem descends from the remote, foreign language of its title to a familiar, authentic language that all soldiers speak and comprehend.

Owen never simply abandoned the poetic tradition he knew and loved. After 1917 his poetry would assimilate to war the images and idiom of the Romantic poets. Thus ‘My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains / my sense’ becomes in ‘Exposure’:

Our brains ache, in the merciless iced east winds that knive us…

Wearied we keep awake because the night is silent…

Low drooping flares confuse our memories of the salient…

Worried by silence, sentries whisper, curious, nervous,

But nothing happens.

The first line carries distorted echoes of a Keatsian voice and an impression of a lost fluency of language and of rhythm. Words (‘Merciless iced east’) sit uncomfortably beside one another, not only conveying the sense of unease but a refusal to let poetry betray the reality of experience. ‘Knive us’ rhymes only half-fittingly with ‘nervous’ as if language is able only partly to convey the reality of trench warfare. ‘My heart aches’ is transformed into ‘Our brains ache’ the vital difference being the movement from the subjective ‘my’ to the collective ‘our’: the we who have the experience.

Owen did not survive the war. For many of the soldiers who did, home meant the loss of that fellowship of ‘our’; they returned to their old lives only to find themselves as strangers there. From his retirement home Harry Patch’s singular, private experience is further enforced by his unusual longevity:

After I came out of the Army I never saw a war film; I never spoke of the war for 80 years. Occasionally we get 40 or 50 people here with a pianist and they sing old wartime songs. It amuses them. They don’t realise the memories they bring back to me:

Keep the Home Fires burning,

While your hearts are yearning

Though the lads are far away

They dream of home.

What ‘they’ don’t realise, of course, is the chasm of difference between the amusing songs of ‘lads’ far away, and the actual experience of that far away dream of home. ‘Exposure’ continues:

Slowly our ghosts drag home: glimpsing the sunk fires, glozed

With crusted dark-red jewels; crickets jingle there;

For hours the innocent mice rejoice: the house is theirs;

Shutters and doors, all closed: on us the doors are closed, –

We turn back to our dying.Since we believe not otherwise can kind fires burn;

Nor ever suns smile true on child, or field, or fruit.

The soldiers’ glimpse of home fires being allowed to die out and of homes from which they find themselves locked out does not, paradoxically, alter their belief in sacrificing themselves in order to keep the home fires burning and they turn back in a body of ‘we’ as if instinctively to the exclusive responsibility of brothers in arms and the real business of war – the dying. This poem is hard to understand, for what it says seems not to make sense. Yet war does not make sense and the best of the war poets realise that paradox and contradiction are their very subjects. If things are inconsistent and confused then poetry can respond to the inconsistency and confusion not explaining, not justifying, not trying to resolve ambiguities, but creatively expressing the otherwise inexpressible. Nor should poetry be expected to provide answers. Owen’s questions reveal others behind and ahead, as if all that questioning can do is breed more questions simultaneously bewildering for the soldier and powerful for the warning poet:

But what say such as from existence’ brink

Ventured but drave too swift to sink,

The few who rushed in the body to enter hell,

And there out-fiending all its fiends and flames

With superhuman inhumanities,

Long-famous glories, immemorial shames –

And crawling slowly back, have by degrees

Regained cool peaceful air in wonder –

Why speak not they of comrades that went under?

(‘Spring Offensive’)

It is a mistake to think of Wilfred Owen as simply speaking for the common soldier, who cannot or will not speak. What he does instead is to incorporate the question ‘Why speak not they’ into the theme of his poetry. The unanswered question is poised at the very end of this poem of Apocalyptic vision. Its position on ‘existence’ brink’ suggests it is finally unanswerable and yet in asking it at all, various and multiple possible reasons ‘why’ echo in the answering silence: the gulf between those who had the experience and those who did not: the impossibility of humanly representing the inhumanity of war, of speaking the unspeakable, of making sense of the senseless; a callous and indifferent world: the silent and unprotesting ranks of soldiers; the fear; the shame; the love for comrades.

In September 1918 Wilfred Owen sent a draft of ‘Spring Offensive’ to Siegfried Sassoon saying ‘Is this worth going on with? I don’t want to write anything to which a soldier would say “No Compris!” In 2002, is Harry Patch’s eighty-year silence his validation?

Share

Related Articles

We cannot just tell parents to read more. To truly improve children’s futures through reading, we need to properly support the adults around them to do so.

Responding to the Department of Education's announcement that 2026 will be a Year of Reading, The Reader's Managing Director Jemma…

Storybarn Book of the Month: Saving the Butterfly

This month, as part of Refugee Week (16-22 June), we've been taking a look back at one of our favourites…

Shared Reading in Wirral Libraries: ‘As a kid people read stories to you but as an adult you lose that – and it’s a fantastic thing to do!’

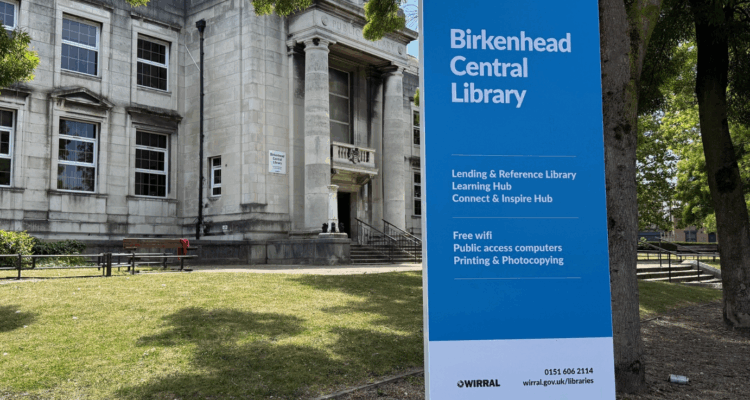

Two Strategic Librarians for Wirral Libraries, Kathleen McKean and Diane Mitchell have been working in partnership with the UK’s largest…