The Cosmos and the Whole Shebang

Jane Davis on the beginning and end of the cosmos, on Science Fiction, and Olaf Stapledon.

Phil and I discussed the likelihood of the end of the world before breakfast on Wednesday morning. What if the CERN scientists were wrong and the collider bang did cause a new cosmos to burst out of the ruins of our old one? And what if that kept happening over and over again in a weird 14 billion year loop? We get this far and they say nothing much’ll happen and then they collide the particles and BANG! Up we go again.

I waited around until 8.00am (when Phil assured me it had happened ‘and everything seems ok.’) Then I set off for The Reader Organisation office, listening, en route, to the Today programme on Radio 4 where (after we heard of the Cabinet having been to Birmingham: wonders, wonders, signs and wonders) we got Andrew Marr in the Control Room at CERN. It was a magnificent piece of radio. Everything seemed so very tentative yet also mildly possible, like the early days of Tim Henman’s Wimbledon career. Something just might be about to happen: something for which we have been waiting for thirty years. We were all cheering. But we realised, too, in our hearts, that maybe it wouldn’t happen. But then perhaps it might. Let’s cheer. Let’s hope it will. Let’s hope. The scientists (as they each spoke they turned out to be a wonderful mix of Ulster, Welsh, English and French) might just manage to bring off what was being billed as the most important scientific experiment since the early Apollo programme.

Which was what it reminded me of as I sat in my traffic jam and listened. Did I really sit on a parquet floor in a primary school assembly hall with 200 other under-11’s and watch ‘one small step for man...?’ I think I did but it is all so long ago... Life is long. And very short. I listened to what Marr called ‘the atmosphere so tense you could it with a ... laser beam’ and I could see the grainy black and white pictures, and hear my grandfather mocking ‘It’s all in a studio! The Yanks have mocked it up! It’s anti-Communist propaganda!’

Later Andrew Marr wondered if Big Bang day would get kids fired up about physics. I think, despite my grandfather’s perfectly reasonable doubts, that it was the Apollo programme that got me interested in Science Fiction. I couldn’t get interested in real science because of the maths or rather my paralysing fearful innumeracy but I did read John Wyndham aged about 11, finishing The Day of the Triffids by torchlight way into the night because I simply could not stop reading and then it went on: Arthur C. Clarke, Robert A. Heinlein, Robert Silverberg. Until at some point I got bored. Later, Joanna Russ and Ursula K. le Guin resurrected my old SF interest when, in my early twenties I went through a period of reading only women but after that I forgot all about my early love, until Doris Lessing introduced me (via 'Some Remarks' at the beginning of Shikasta) to the biggest daddy of all Sci Fi books: Last and First Men, by Olaf Stapledon.

For Big Bang Day, Big Bang Week, Big Bang Year, this is the man to read. He is the biggest. Cosmology? Infinity? He’s got it by the billion squared. He tells our human story from the primordial soup days to the way past the end of the our universe, and many other universes.

But he doesn’t think of it as Science Fiction, just fiction. In the Preface to the 1930 edition, Stapledon writes:

This is a work of fiction. I have tried to invent a story which may seem a possible, or at least not wholly impossible, account of the future of man; and I have tried to make that story relevant to the change that is taking place today in man's outlook.

To romance of the future may seem to be indulgence in ungoverned speculation for the sake of the marvellous. Yet controlled imagination in this sphere can be a very valuable exercise for minds bewildered about the present and its potentialities. Today we should welcome, and even study, every serious attempt to envisage the future of our race; not merely in order to grasp the very diverse and often tragic possibilities that confront us, but also that we may familiarize ourselves with the certainty that many of our most cherished ideals would seem puerile to more developed minds. To romance of the far future, then, is to attempt to see the human race in its cosmic setting, and to mould our hearts to entertain new values.

...The activity that we are undertaking is not science, but art; and the effect that it should have on the reader is the effect that art should have.

‘The human race in its cosmic setting.’ I loved that – the enormous size of it.

It was an amazingly lucky stroke for me as a young post-grad to discover that Olaf Stapledon--despite his exotic northern name--had been a lecturer in the Extension Studies programme at the University of Liverpool. Not only that, but all his papers had been donated to our very own Sydney Jones Library. Not only that, but they had not (I’m talking 1983) yet been catalogued. Not only that, but when I arrived breathless with excitement in SJL Special Collections, some of them hadn’t even been lifted out of the original, dusty, old cardboard boxes Olaf himself (probably) packed them into before carrying up to his attic. Some of the boxes had string round them. I undid it, thinking: he tied this careful knot.

Reading through that stuff (almost all of it totally unrelated to my PhD thesis) was an experience of immense magnitude. It was like getting involved with a ghost. There he was--everywhere and in all sorts of ways--but I couldn’t see him or touch him, though I could sense him, feel him and hear him but then I couldn’t quite feel him or hear him. Yet he was in my mind. I knew him.

One day I found a letter, hand typed on one of those old sit up and beg typewriters, from H. G. Wells, and there was H. G. Wells’ signature in heavy ink, and (as I remember it) it was a kind letter, praising (was it? My memory isn’t too good) Last and First Men but not praising it with huge generosity and, I think, a little egotistically drawing Stapledon’s attention to something Wells had himself recently published or written. I remember it as being on hotel notepaper. It was a wonderful moment, holding it, with the box in front of me, and no one telling me not to touch it. Two great giants of Sci Fi seemed before my eyes. Yes, I think I saw them. Both dead, they were in some sense present.

There’s an awful lot we can’t see. Think of all that dark matter: we don’t even know what it is, only that it is most of what’s here. Three cheers for the particle colliders then and for more people taking ‘A-level' physics. They are going bring a little more of that darkness into the light.

Posted by Jane Davis

Share

Related Articles

We cannot just tell parents to read more. To truly improve children’s futures through reading, we need to properly support the adults around them to do so.

Responding to the Department of Education's announcement that 2026 will be a Year of Reading, The Reader's Managing Director Jemma…

Storybarn Book of the Month: Saving the Butterfly

This month, as part of Refugee Week (16-22 June), we've been taking a look back at one of our favourites…

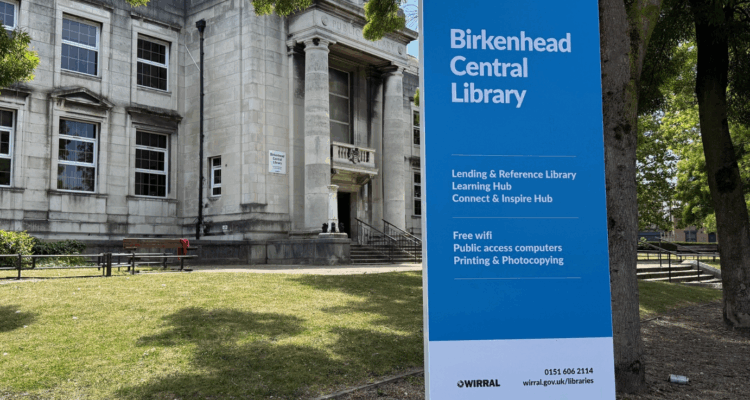

Shared Reading in Wirral Libraries: ‘As a kid people read stories to you but as an adult you lose that – and it’s a fantastic thing to do!’

Two Strategic Librarians for Wirral Libraries, Kathleen McKean and Diane Mitchell have been working in partnership with the UK’s largest…