Feeling it: Reading the emotions of others

Discussions on literature and empathy continue to buzz around The Reader HQ following Obama's sentiments on reading for empathy, our founder and director Jane Davis reflects on how literature can help us connect with others.

When, in December, I was invited to record a conversation about empathy with Sir Peter Bazalgette, outgoing chair of Arts Council England, I found Dicken’s greatly underestimated, somewhat over-caricatured novella, A Christmas Carol in my mind. It’s a study in the loss and regeneration of empathy, which Dickens would have called ‘fellow-feeling’. Can literature can help teach us this? In a recent piece in The Guardian, Sir Peter writes:

"Jonathan Gottschall, in his book The Storytelling Animal (says): “The constant firing of our neurons in response to fictional stimuli strengthens and redefines the neural pathways that lead to skillful navigation of life’s problems.”

From The Tiger Who Came to Tea to Pride and Prejudice, we’re a species of story tellers and story listeners. And it’s not just to satisfy our love of entertainment. Keith Oatley is a novelist but he’s also a cognitive psychologist. He carried out a study of people reading novels. It concluded that regular consumption demonstrably develops empathy and makes us more adept at reading the emotions of others.

Sir Peter Bazalgette, The Guardian

I think I agree about ‘reading the emotions of others’ but this is a complicated area. In an earlier programme in the series, primatogist Frans de Waal said, empathy "starts by being affected by the emotions of others…" That made me wonder what happens if a trauma prevents the creature being so ‘affected’. Someone in that state, like Scrooge, would be very unlikely to want to read fiction. Bah humbug, he’d cry. Warren Adler, writing in The Huffington Post, tells us:

"There is ample statistical evidence showing that adult women read more novels than men, attend more book clubs than men, use libraries more than men, buy more books than men, ... If, as a demographic, they suddenly stopped reading, the novel would nearly disappear."

Warren Adler, Huffington Post

There’s an evolutionary biology argument (maternal feeling) for more highly developed empathy in women which De Waal touches on slightly, which may lie behind this universally acknowledged truth about women reading more fiction than men. But here and now, whatever our primate past, we all need to feel and know our own and others’ feelings.

Indeed the future of humanity may depend on our ability to do so. That’s why Ashoka is now building a network of schools where empathy and change-making are learned.

How does Scrooge learn fellow-feeling? Against his controlling adult will he is first made to feel for himself, as the First Ghost takes him back to his early, unhappy childhood:

"They went, the Ghost and Scrooge, across the hall, to a door at the back of the house. It opened before them, and disclosed a long, bare, melancholy room, made barer still by lines of plain deal forms and desks.

At one of these a lonely boy was reading near a feeble fire; and Scrooge sat down upon a form, and wept to see his poor forgotten self as he used to be.

Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol

Recognising and feeling for that forgotten child-self, Scrooge is moved to think of other children:

"Then, with a rapidity of transition very foreign to his usual character, he said, in pity for his former self, ``Poor boy!'' and cried again.

``I wish,'' Scrooge muttered, putting his hand in his pocket, and looking about him, after drying his eyes with his cuff: ``but it's too late now.''

``What is the matter?'' asked the Spirit.

``Nothing,'' said Scrooge. ``Nothing. There was a boy singing a Christmas Carol at my door last night. I should like to have given him something: that's all.''

Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol

There are three movements here: Scrooge felt his feelings long ago when he was child; he becomes conscious of those feelings (‘he wept to see his poor forgotten self as he used to be’) and then he translates from his own ‘poor boy’ self to any other ‘poor boy’.

Literature, like Scrooge’s Ghost, can take us to parts of ourselves we have forgotten or may not wish to see. Over many years of reading with others I have seen people powerfully moved by such experiences; the young student who said to me, of Middlemarch, ‘I don’t associate with Dorothea at all, I am Fred Vincy’, or the men who looked up in pain as I read Jacob Marley’s words in a grim hostel canteen one Christmas, ‘these are the chains I forged in life…’ Yet I can recall fewer than a handful of people unwilling to face the recognitions that literature offers.

It is partly because we need to see our own experience reflected in this way that prison libraries are full of true crime books. But we are all more than the sum of our crimes. Prisons need poetry! Great literature offers the most truthful mirrors for the complexity of being human.

‘That’s me, that is…’ said a woman in a Shared Reading group in a prison, reading Charles Bukowski’s poem Bluebird. The poem is full of difficult adult mess. This woman, despite her underdeveloped literacy skills, knew those complexities as well as anyone.

‘It's got my belly churning. He's hard-faced and doesn't want people to see he has something special going on. It's like me really...that one...it got me, man!’

Shared Reading Group Member

Reading a poem for the first time with pained pleasure, this prisoner felt the connection viscerally – rubbing her stomach as if she’d been punched, ‘It got me, man’. How does this help create empathy?

It’s not so much that the poem creates the experience of someone else’s feelings but that it gives the reader a language in which she can recognise her own. From that place, any reader might move to, ‘and if I feel this…so might you.’

Get involved and be part of the story...

To find out more about The Reader's work in the Criminal Justice sector visit our website: www.thereader.org.uk

Share

Related Articles

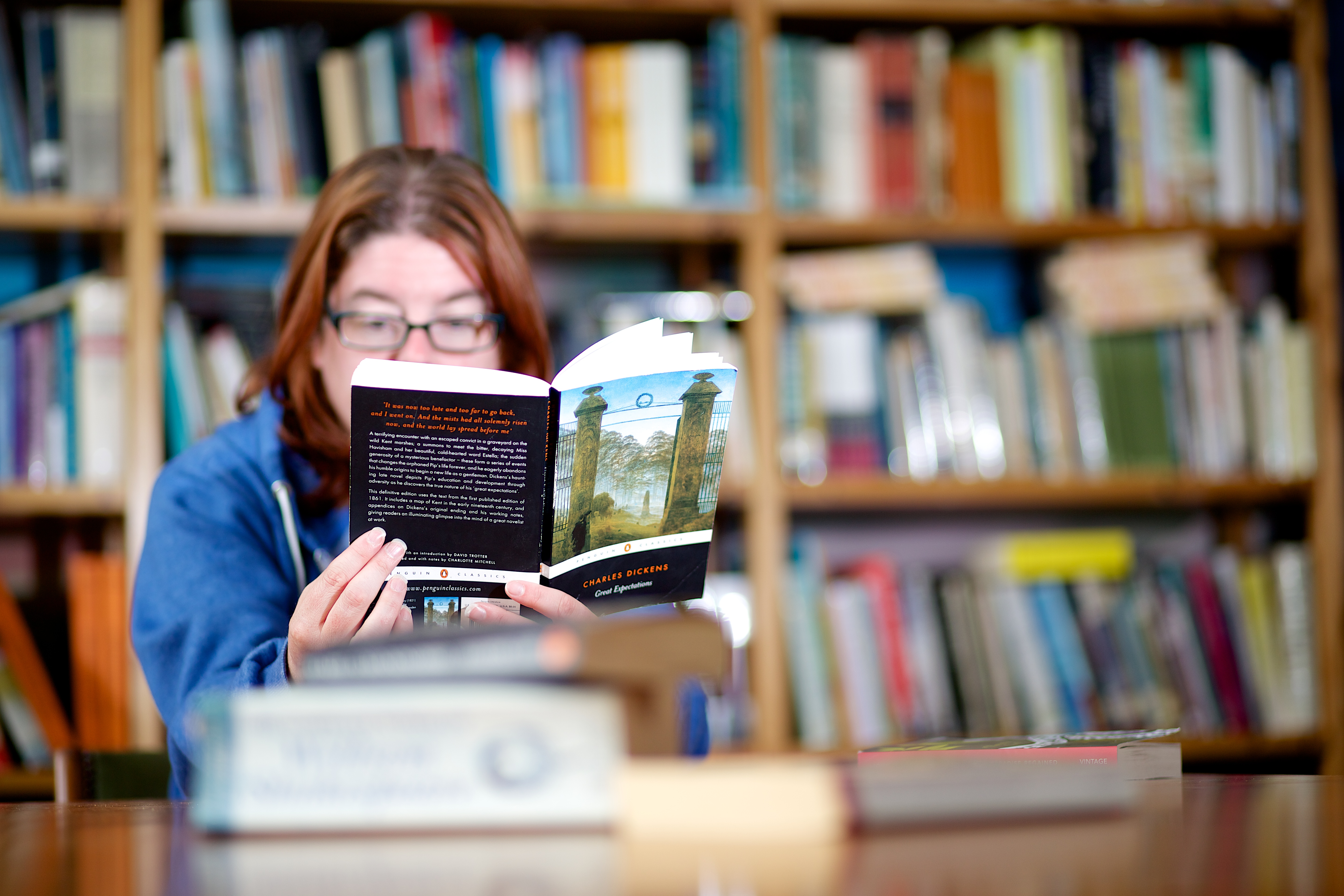

Shared Reading in Wirral Libraries: ‘As a kid people read stories to you but as an adult you lose that – and it’s a fantastic thing to do!’

Two Strategic Librarians for Wirral Libraries, Kathleen McKean and Diane Mitchell have been working in partnership with the UK’s largest…

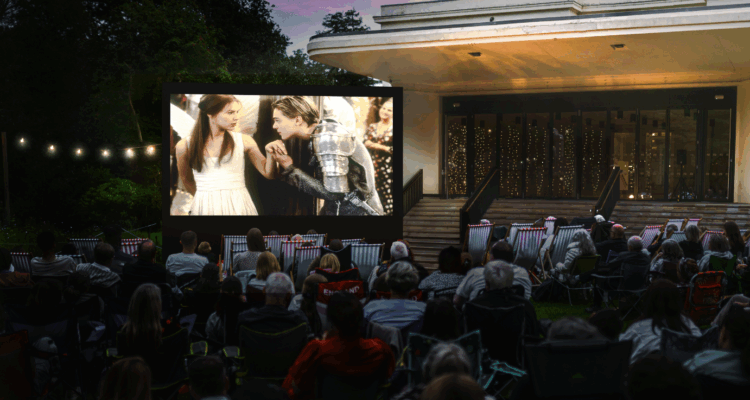

Open Air Cinema FAQ’s

If you were able to snap up tickets to our brand new Open Air Cinema, check below for any queries…

New Liverpool open air cinema brings movies to the Mansion

NEW FOR 2025: Eight handpicked films will hit the big screen in Calderstones Park this summer as national Shared Reading…