Inside Time: The Send-Off in HMP Liverpool

Throughout the UK we are sharing reading in prisons and secure Criminal Justice settings, with the reading and discussion of great literature creating the opportunity for offenders and ex-offenders to transform their attitudes, thinking and behaviour, improve their health, wellbeing and interaction and increase levels of self-confidence and self-reflection.

Each month highlights from shared reading sessions are featured in Inside Time, the national newspaper especially for prisoners in the UK, and we'll be publishing the articles here on The Reader Online after they've been featured in the paper.

The latest article comes from Amanda Brown, who is in charge of the strategic development of our Criminal Justice projects, and her 'Read and Relax' group at HMP Liverpool. The group are discussing The Send-Off by Wilfred Owen:

Down the close, darkening lanes they sang their way

To the siding-shed,

And lined the train with faces grimly gay.

Their breasts were stuck all white with wreath and spray

As men's are, dead.Dull porters watched them, and a casual tramp

Stood staring hard,

Sorry to miss them from the upland camp.

Then, unmoved, signals nodded, and a lamp

Winked to the guard.So secretly, like wrongs hushed-up, they went.

They were not ours:

We never heard to which front these were sent.

Nor there if they yet mock what women meant

Who gave them flowers.Shall they return to beatings of great bells

In wild trainloads?

A few, a few, too few for drums and yells,

May creep back, silent, to still village wells

Up half-known roads.- Wilfred Owen

K, T, W, M, L, D and P discuss this with me. All listen while I read, after which there is silence.

“Troops going to war. Very poignant.” K sighs. “Old men make wars, young men fight them.”

M, a young man, stabs at the page and looks up.

“I can see them – on the trains. Grimly gay - gay meant happy then. They had to go. Didn’t want to go.”

“It’s the title that hits me – The Send-Off – it’s like a funeral,” says P. “all white with wreath and spray…”

“As men's are, dead,” adds L. He leans forward, animated. “Why would they be getting onto a train if a siding shed? They’re not alive!”

Others need to consider this. D frowns.

“That’s interesting, what you’re saying,” says K. “I hadn’t seen that.”

There is lively debate here. D suggests lines of the poem which seem to contradict L. Lee remains adamant.

“That’s the beauty of poetry,” he claims. “You see one thing, I see something else.”

When they pause, W speaks quietly.

“If I didn’t know Wilfred Owen was writing in WW1, I’d have said it’s about the Jews being sent to concentration camps. I can see that.”

We exclaim, then, about the possibilities of the poem, unknown by the writer, provided by history.

“Owen knew nothing about WW2. We can’t read his poetry without knowing about it.”

“Makes me think about taking my granddad, who’d been in the war, to see Saving Private Ryan. That opening sequence – he said it was just like that.”

“Secretly, like wrongs hushed-up, they went.” I repeat. Then, all at once, everyone is speaking.

“They don’t know where they’ve going. They’re young. Leaving their homes, their wives and girlfriends.”

“That’s why the women gave them flowers.”

“’Don’t forget me!’ – that’s what the flowers mean. That’s like my missus. She sprayed my clothes with her perfume before I came here.”

“My ex-father-in-law was in the war. He was from Scotland. He was shipped out of Liverpool and his sisters came all the way down to Liverpool to see him off. They bought him flowers – he told me that.”

I reread the lines: Nor there if they yet mock what women meant/who gave them flowers and suggest that maybe the women’s message was ‘Look after yourself. Come back to me.’

“The wives won’t know where their men are – no-one knew,” says M.

“They don’t know where their letters are going. They write, but then they hear nothing,” says T.

I wonder about the question in the poem: Shall they return to beatings of great bells/ In wild trainloads?

“Because they won’t be coming back,” says P. “Most of them won’t.”

“Just a few, maybe,” adds D. “No parades. No cheering.”

We discuss the scenes in Wootton Bassett - the silent respectful crowds.

“Creep back, silent, to still village wells,” reads L. This is their spirits coming back!”

“I don’t see that,” says D. “But I can understand where you get that from.”

“Reading like this – it’s like splintered glass,” says K. “It’s spread out in so many different directions.”

“I think this poem is the easiest to understand of all the ones we’re read,” says D.

“It means something to all of us,” says K. “We feel it.”

Discover more about shared reading in prisons and Criminal Justice settings on our website: https://www.thereader.org.uk/what-we-do-and-why/criminal-justice

Nick Benefield, former NHSE PD Advisor and Joint Head of NHSE/NOMS Offender PD Team, and Lord Alan Howarth, All Party Parliamentary Group for Arts, Health and Wellbeing, will be discussing the effect of shared reading in secure mental health settings at Better with a Book, The Reader Organisation's 2014 National Conference on Thursday 15th May at the British Library Conference Centre, London. Head to our website to discover how you can book your place: https://www.thereader.org.uk/events/conference

Share

Related Articles

Storybarn Book of the Month: Saving the Butterfly

This month, as part of Refugee Week (16-22 June), we've been taking a look back at one of our favourites…

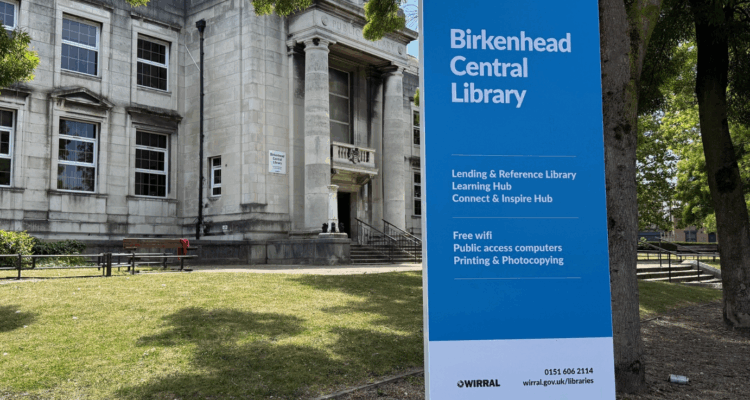

Shared Reading in Wirral Libraries: ‘As a kid people read stories to you but as an adult you lose that – and it’s a fantastic thing to do!’

Two Strategic Librarians for Wirral Libraries, Kathleen McKean and Diane Mitchell have been working in partnership with the UK’s largest…

Open Air Cinema FAQ’s

If you were able to snap up tickets to our brand new Open Air Cinema, check below for any queries…