Literature of Depression

In 2005 Monica Janssens was diagnosed with panic disorder and severe depression and admitted to the Priory Hospital. Monica has written a novel inspired by her experience and about the stigma that still attaches to depression. Here she explains how reading helped in her recovery.

"O let me not be mad, not mad, sweet heaven! Keep me in temper: I would not be mad."

--William Shakespeare, King Lear, Act I, Scene V.

In the midst of a severe depressive attack it takes a Herculean effort to read the label on an anti-depressant bottle, let alone absorb the page of a book and remember what you’ve just read. But that doesn’t mean literature doesn’t have a place in the lives of the mentally ill. From both experience and observation, I would argue the contrary and, judging from the 7,700 titles listed by Amazon under "Depression", I’m not alone. The panic attack which landed me in the Priory in the summer of 2005 was indescribably painful. For some peculiar reason King Lear (an old favourite) came into my mind and only by going to bed with the book, and reciting some of the verse, could I finally cry myself to sleep.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. If you’re feeling desperate and suicidal, reading King Lear is hardly going to cheer you up. But expecting literature (no matter how powerful) to alleviate depression when it’s in full swing is unrealistic. What literature can do, however, is make us feel less alone. That counts for a lot because depression is isolating and it’s the isolation which, more than any other single factor, leads to suicide; curiously, during both world wars suicide rates in England fell dramatically.

The concept of depression was formulated less than a hundred years ago, yet it’s interesting that some of the best literature describing the condition was written before it was recognized. Take Keats’s poetry. If Keats had been alive today he would probably have been diagnosed with depression: nobody can come up with "Where but to think is to be full of sorrow/And leaden-eyed despairs" and not be a sufferer. Keats, of course, was a Romantic. The Romantics were influenced by Goethe, whose semi-autobiographical tale The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) ended in a suicide and supposedly led to 2,000 readers doing the same thing. At university I took Russian Literature in Translation as an ancillary to my English degree, which may have been a sign of my depressive leanings. The Russians have a reputation for producing melancholic literature of the highest order; it seems deeply ingrained in their psyche. Chekov’s The Seagull ends in suicide, as does Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. Both works were thought to be influenced by Hamlet--a portrayal of the archetypal, inward-looking depressive if ever there was one--in which Shakespeare, like Dostoevsky, focuses in painstaking detail on the central character’s mental anguish. Modern English writers take a more understated approach to describing depression. Graham Greene’s chief protagonists are invariably tortured souls with self-destructive tendencies (The Power and the Glory, The Quiet American, The Heart of the Matter), while the alcoholic Jean Rhys was haunted by Mr Rochester’s first wife in Jane Eyre and wrote a prequel, Wide Sargasso Sea, exploring the causes of her derangement.

Nowadays, the literature of depression is divided into two main categories: self-help books and either confessionals or autobiographically-based novels. Sylvia Plath’s novel The Bell Jar falls into the second camp and is a rewarding read, but if the act of writing is cathartic it was not cathartic enough to prevent Plath committing suicide. The same is true, of course, of Virginia Woolf who describes so tenderly in Mrs Dalloway the horrors of shell shock, now known as post-traumatic stress disorder.

I’m not sure what the depression self-book market is worth, though judging by the number of titles available it must be a lot. For the first six weeks of my therapy I couldn’t read even half a book and this is where self-help books score: you can dip in and out of them, take it one step at a time. You don’t always have to start at the beginning, either. The one that worked for me is Tim Cantopher’s Depressive Illness: The Curse of The Strong because it seemed to know exactly how I was feeling. It didn’t beat me up for it. In fact, it made me feel special--sensitive and responsible--because I had the wretched illness in the first place. I’d read a page a day, then re-read it the next day.

Part of my treatment involved creative writing classes. We’d have a picture to describe in a set time, then we’d each be invited to read it out. That was the nearest we got to shared reading, or, given our low concentration thresholds, any kind of reading. With the research being done on the therapeutic benefits of reading aloud, I believe there’s a strong case for making it more of a feature in rehabilitation and psychiatric hospitals.

Share

Related Articles

Open Air Cinema and Theatre FAQ’s

If you were able to snap up tickets to our Open Air programme this summer, check below for any queries…

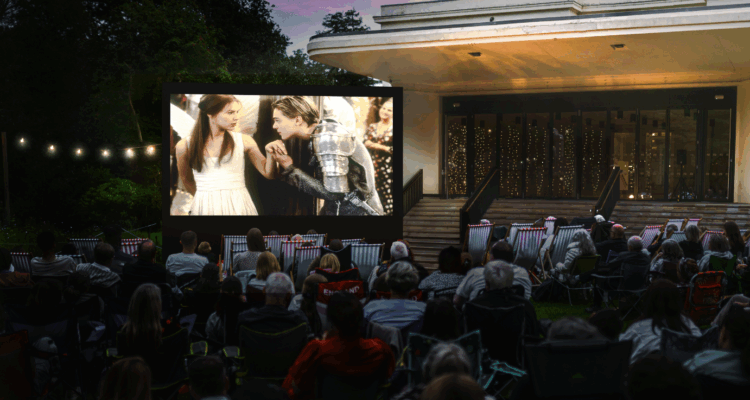

New Liverpool open air cinema brings movies to the Mansion

NEW FOR 2025: Eight handpicked films will hit the big screen in Calderstones Park this summer as national Shared Reading…

A breath of fresh air! This summer’s outdoor and cultural events at our Calderstones Park home

The Reader serves up a giant scoop of summer arts and entertainment from three special summer garden parties with special…