The Reader’s Commitment to Equality and Inclusion: The Reader Magazine

This article is taken from Issue 72 of The Reader Magazine, for more articles, interviews, stories and poems from this biannual publication - become a subscriber.

Our work is based on the belief that all great literature can provide points of connection for and between individuals. ‘Great literature’ is any literature that makes the reader feel more and think more; makes the world seem bigger; makes our sense of possibility and our sphere of sympathies greater than before. We believe, as Bernardine Evaristo wrote recently, ‘literature can connect us to each other and foster and express our shared humanity’. The Reader grew out of the conviction that literature can help people connect to one another across the unclassifiable diversity of individuality, as well as across time, space, class, race, gender and many other identity categories. For nearly 20 years, The Reader has worked to reach people who have been denied this connection to literature, blocked by educational or socio-economic barriers, or to those who have only experienced literature as something to be detachedly examined in the classroom.

‘What do I have in common with Olive Kitteridge, a salty old white woman who has spent her entire life in Maine? And yet, as it turns out, her griefs are like my own. Not all of them. It’s not a perfect mapping of self onto book – I’ve never met a book that did that, least of all my own. But some of Olive’s grief weighed like mine. Certainly I might turn from a writer like Elizabeth Strout toward a writer like Toni Morrison and find our griefs more closely aligned, for obvious reasons like race and class, which two contingencies do so much to form a person’s experience and therefore their sensibilities. But what passed between me and Olive was not nothing. I am fascinated to presume, as a reader, that many types of people, strange to me in life, might be revealed, through the intimate space of fiction, to have griefs not unlike my own. And so I read.’

Zadie Smith

The Reader’s work is based on the same presumption. And so we read, together, aloud.

The past weeks have brought crisis to us all, and crisis has forced awakenings and re-evaluation. The ravages of the pandemic have demanded painful readjustment, cuts and losses at The Reader. The protests erupting around the world in response to the latest violent instances of systemic racial injustice demand immediate and far-reaching response from The Reader too.

‘That was the sort of crisis which was at this moment beginning in Gwendolen’s small life: she was for the first time feeling the pressure of a vast mysterious movement, for the first time being dislodged from her supremacy in her own world, and getting a sense that her horizon was but a dipping onward of an existence with which her own was revolving.’

From Daniel Deronda by George Eliot

The work that is demanded of us now involves a heightened consciousness of the racialised assumptions and biases that may have, however unconsciously, unpinned our practises to this point, and a wholehearted, rigorous overturning of those assumptions and biases. We are committed to undertaking this work and it will include all of our community – our employees, volunteers, customers, trustees and partners.

But any lasting change must go deeper than reformations to policy or practice; these reformations must take place at the level of sense and feeling. And so, we read. The requirements of any piece of literature – poem, short story, drama or novel – chosen to be read in a Shared Reading context is: ‘Does it make us think and feel something more, something we cannot perhaps put into words as part of our everyday experience?’ This requirement will not change, but we are now actively seeking out literature by writers of diverse cultures and backgrounds, which will bring us that heightened consciousness or wider vision that we need. Entering these ‘intimate spaces of fiction’ alone and in private would be valuable, but entering them as part of a Shared Reading group brings the gut reactions and emotional responses they inspire to light, to be understood and valued.

There are many Shared Reading groups taking place in challenging environments, and we know – because the members of the groups have told us – that reading together offers the space to confront difficult, thorny and painful experience. Our practice of Shared Reading encourages group leaders to trust the literature being read, and trust that reading it aloud and talking about it together will lead to the creation of new and deeper meanings and connections. We also learn to trust the moments when raw emotion wells up, because these moments also bring release and a remoulding of our ideas.

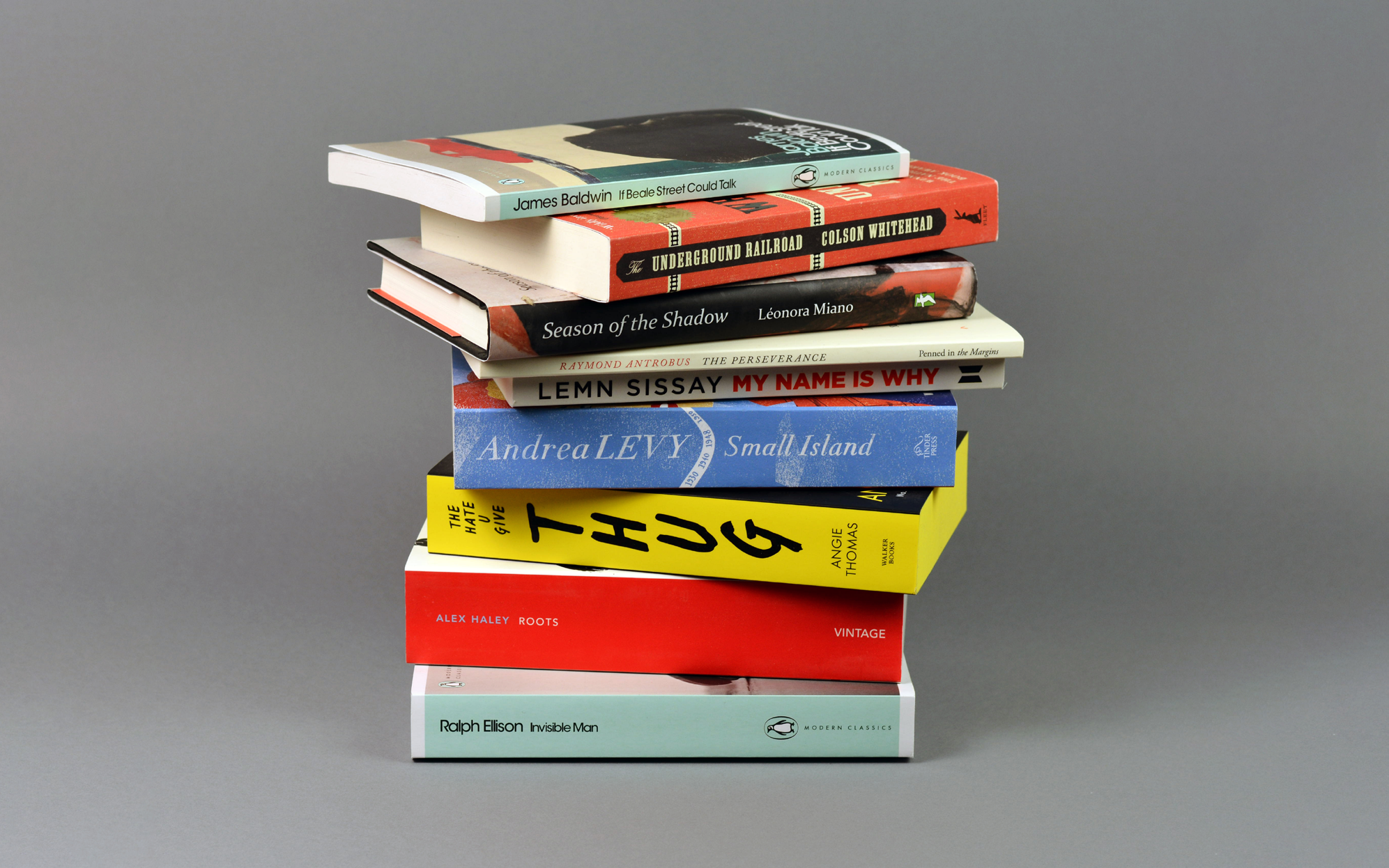

In this moment of reckoning then, we will find and share with each other the great literature that, through the keenly felt personal responses they inspire in any reader, will light the way forward. Included in this issue and listed below is some of the literature by Black writers that we are reading together now in order to get that sense of our horizons, dipping onwards. The list below is made up of stories and poetry by Black writers which are already used in Shared Reading groups, alongside newer works that will be read in future groups. It is by no means an exhaustive list or the full extent of the work we mean to do. The Reader’s commitment to this work of equality and inclusion is the same commitment we make in our Shared Reading training for group leaders, and the same made implicitly by anyone who turns up to a group, week after week: we will keep reading, keep learning.

‘Starting a story together is like when you start out on a journey – starting out with everyone and getting to the end of that journey together. It takes you out of your world, but it can also have a bearing on your life as well. You’ll see how a character deals with the world in a certain way and you think… “well, maybe I could learn something from that?”’

Shared Reading group member

Poems

‘Boston Year’ by Elizabeth Alexander

‘Alone’ by Maya Angelou

‘Jamaican British’ by Raymond Antrobus

‘Truth’ by Gwendolen Brooks

‘Some Bright Elegance’ by Kayo Chingonyi

‘Aunt Ida Pieces a Quilt’ by Melvin Dixon

‘Mother to Son’ by Langston Hughes

‘In My Country’ by Jackie Kay

‘Statues’ by Derek Walcott

Poetry collections

Alternative Anthems by John Agard

The Perseverance by Raymond Antrobus

The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion by Kei Miller

A Portable Paradise by Roger Robinson

The Vintage Book of African American Poetry edited by Michael S. Harper and Anthony Walton

Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry edited by Camille T. Dungy

Short stories

‘Apollo’ by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

‘Recitatif’ by Toni Morrison

‘Everyday Use’ by Alice Walker

Novels and memoirs

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

If Beale Street Could Talk by James Baldwin

Kindred by Octavia Butler

The Beautiful Struggle by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Small Island by Andrea Levy

Roots by Alex Haley

Red Dust Road by Jackie Kay

Season of the Shadow by Léonora Miano

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

My Name Is Why by Lemn Sissay

White Teeth by Zadie Smith

The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

Share

Related Articles

Reader Revisited: Jane Davis in Conversation with Jeanette Winterson

We're taking a trip down memory lane and revisiting articles from The Reader Magazine. This article first appeared in issue 44.…

Reader Revisited: An Interview with Het Lezerscollectief (The Readers’ Collective)

We're taking a trip down memory lane and revisiting articles from The Reader Magazine. This article first appeared in issue 73.…

Reader Revisited: An Interview with Mark Rylance, actor and writer of ‘I Am Shakespeare’

We're taking a trip down memory lane and revisiting articles from The Reader Magazine. This article first appeared in issue 29.…