Recommended Reads: James Ellroy, The Black Dahlia

The Black Dahlia (1987) is a fictionalised account of the notorious unsolved murder of Elizabeth Ann Short in Los Angeles in 1947. Short’s tortured body was found on an abandoned lot on January 15 and became the focus of a media frenzy and one of the biggest police investigations in California history. Short, who was often seen in nightclubs wearing sexy black dresses much like a femme fatale, came to be dubbed the Black Dahlia after the Raymond Chandler scripted film noir starring Alan Ladd, The Blue Dahlia (1944).

The Dahlia mythology has spawned numerous conspiracy theories as to the identity of her killer. Yet, while Ellroy’s gripping take on the case did not bring anyone closer to uncovering the murderer, it did help forge Ellroy’s greatest strengths as a writer. His depiction of post-war L.A. is unmatched amongst American crime writers, a utopian spectacle masking a cauldron of corruption, organised crime, and ethnic tension: ‘It’s a boomtown populated by psychically maimed misfits running from World War II. It’s a fiend habitat.’ This is the Los Angeles setting Ellroy grew up in, but the plot also parallels his life. The unsolved murder of his mother Geneva Hilliker Ellroy has striking similarities to the Dahlia case.

The story of The Black Dahlia is told through the first person narrative of Dwight ‘Bucky’ Bleichert, a warrant squad cop with the L.A.P.D. who strikes up an unlikely friendship with fellow officer Lee Blanchard, and his beautiful girlfriend Kay Lake. Bleichert and Blanchard find themselves on the Dahlia case seventy-five pages into the novel. Before then, Ellroy weaves a complex back-story involving the zoot suit riots of 1943, a politically staged boxing bout, and Blanchard’s impressive list of ‘collars’. As is typical of Ellroy, the violence is graphic and to the point: ‘the breasts were dotted with cigarette burns, the right one hanging loose, attached to the torso only by shreds of skin’. His portrayal of Elizabeth Short’s fate is explicit but never exploitative, her cadaver is described scientifically, ‘dotted’, ‘hanging’, and ‘attached’.

Violence alone cannot make a great crime novel, and whilst this dark tale may not be for those of sensitive tastes, Ellroy’s writing style and interweaving of storylines is subtle and assured. The zoot suit riots are an explosion of underlying urban tension, the boxing bout is motivated by political corruption and self-interest and Blanchard’s past collars become his undoing when Bleichert uncovers his dark nature. Ellroy is less interested in the buddy-buddy relationship of Bleichert and Blanchard, than he is in the unusual trinity of Bleichert, Blanchard, and Kay. For a character who grapples so much with the nature of evil, Bleichert finds himself acting as a kind of alternative husband in an unholy marriage. The three friends do everything together: work, play, and fight. Ellroy complicates matters even further when Bleichert becomes romantically involved with Madeleine Cathcart Sprague, a Black Dahlia look-alike whose family may be involved in the murder. The Dahlia becomes the epicentre for these characters soul, forging unlikely alliances, uncovering evil and offering redemption in equal measure.

James Ellroy was ten years old at the time of his mother’s murder. He first came across the Black Dahlia case a year later in Jack Webb’s sensationalist true crime book The Badge. The Black Dahlia is not autobiography and it is not history, though Ellroy leaves many of the factual details of the case unchanged. It is not even entirely original as fiction: John Gregory Dunne’s, True Confessions (1977) is a fine fictional rendering of the case, and an influence on Ellroy. Whatever category The Black Dahlia falls into, autobiography, history, fiction, the final and most unusual alliance to appear is that of Elizabeth Ann Short, Geneva Hilliker, and James Ellroy. From it Ellroy has produced one of the finest American crime novels of the last fifty years.

By Steven Powell

Share

Related Articles

April’s Monthly Stories and Poems

The clocks have not long changed to herald the longer hours of daylight, making us consider the passage of time…

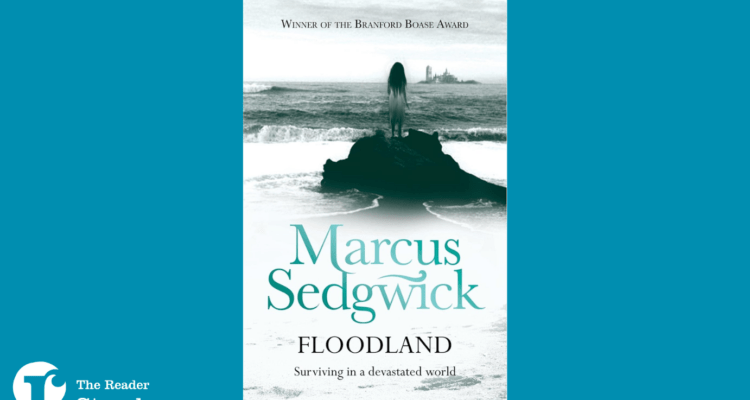

The Storybarn Selects… From The Reader Bookshelf

Our last deep dive into the 2023/24 Children and Young People's Reader Bookshelf is a review of Floodland by Marcus Sedgwick…

March’s Stories and Poems

March’s stories, extracts and poems have been chosen on the theme ‘Moving on’, which perhaps feels especially relevant as we…